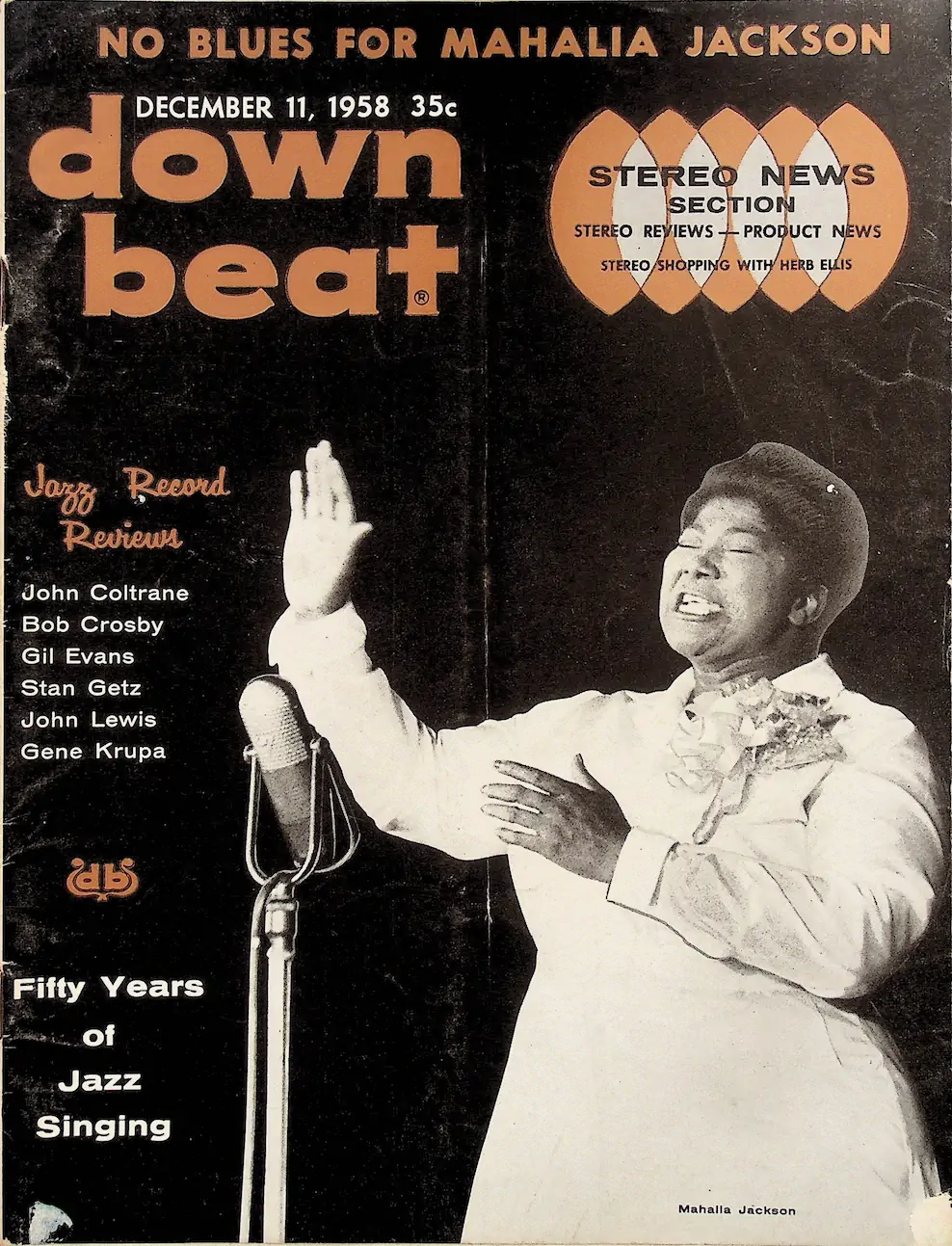

Jazz Magazine - downbeat

December 11, 1958

Downbeat is a US-based jazz and blues magazine that is widely considered the most influential and widely read publication of its genre. Founded in Chicago in July 1934, it has become a central institution in the world of jazz

History and Significance

DownBeat was started by Albert J. Lipschultz, an insurance salesman who originally saw the magazine as a way to advertise his services to musicians. The name "DownBeat" refers to the first beat of a measure, which a bandleader typically signals with a downward motion.

Initially published monthly, the magazine's growing popularity led it to be published twice a month starting in 1939, and then every two weeks from 1946. Since April 1979, it has returned to a monthly schedule. It has documented the evolution of jazz from the big band era through bebop, fusion, and beyond.

Often called the "Bible of Jazz," DownBeat has significantly influenced the careers of many musicians. Over the years, its writers have included renowned critics and journalists like Leonard Feather, Nat Hentoff, and Ira Gitler.

Content and Recurring Features

Interviews and Articles

The magazine features in-depth interviews with leading musicians and informative articles on the history of jazz and blues.

Reviews

A key component is its comprehensive reviews of albums and live performances, which are rated on a 5-star system.

„Blindfold Test"

One of the magazine's most famous columns, where jazz musicians are asked to listen to and guess recordings by other artists without knowing who they are.

Polls: Since 1937, DownBeat has conducted its annual "Readers Poll," and since 1953, its "Critics Poll" in various categories. The results of these polls are considered among the most important awards in the jazz world and lead to induction into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame.

Downbeat Today

Today, the magazine is published by Maher Publications Inc. and remains an essential source of information for jazz and blues enthusiasts worldwide. It continues to cover industry news, offer insights into musicians' work, provide festival reports, and analyze musical trends.

© downbeat 1958

Article

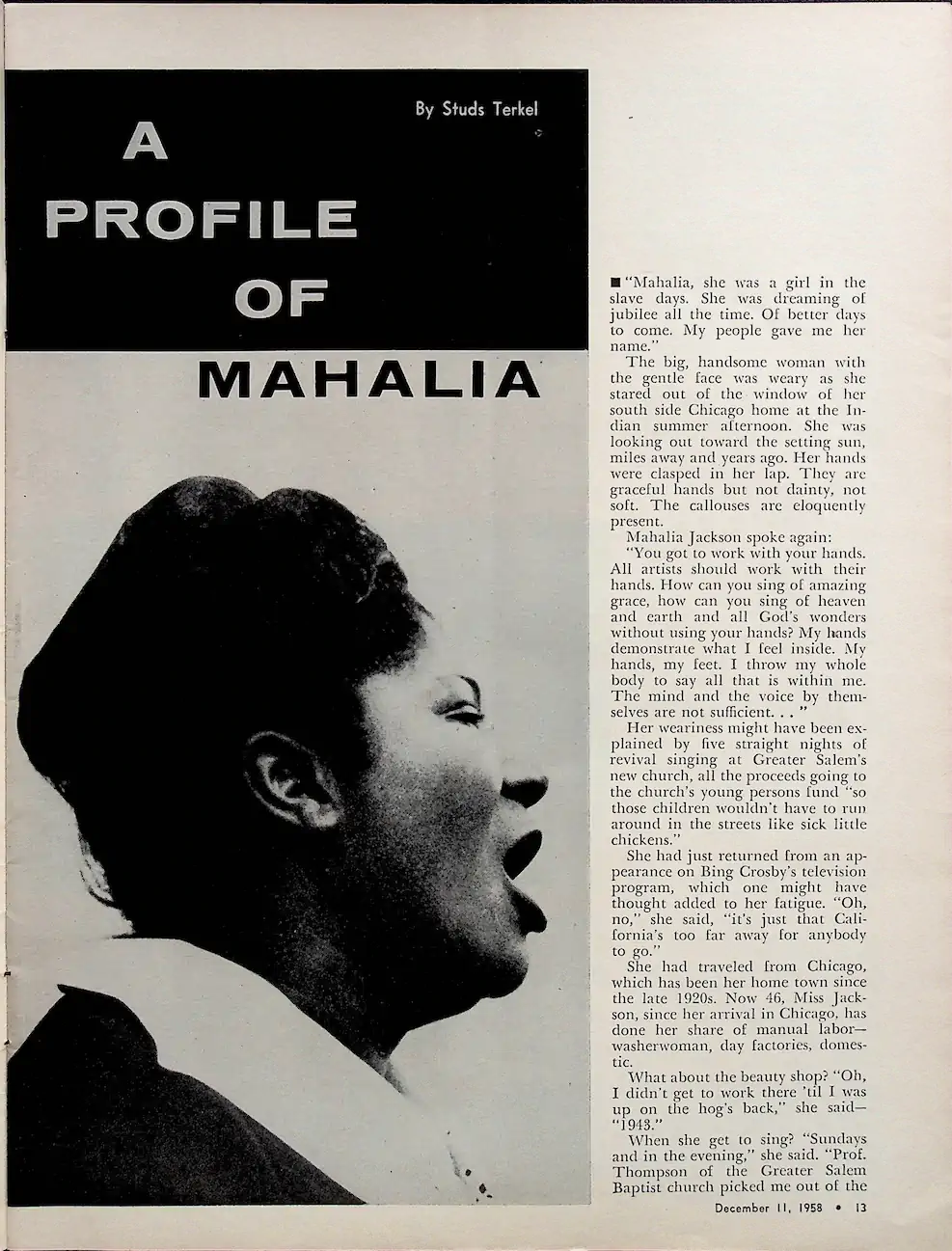

Mahalia was a girl who had been enslaved. She always dreamed of “jubilee all the time,” of better days to come. My father gave me her name.s, offer insights into musicians' work, provide festival reports, and analyze musical trends.

The tall, beautiful woman with the gentle face looked tired as she gazed out of the window of her house on the south side of Chicago one late summer afternoon.She looked toward the setting sun, miles away and many years ago. Her hands were folded in her lap. They are graceful hands, but not delicate, not soft. The calluses are clearly visible. Mahalia Jackson spoke again: “You have to work with your hands. All artists should work with their hands. How can you sing of amazing grace, how can you sing of heaven and earth and all the wonders of God without using your hands? My hands show what is inside me. My hands, my feet. I throw my whole body into it to say everything that is inside me. The spirit and the voice alone are not enough.”

Her exhaustion may have been due to five nights of revival singing at the new Greater Salem Church, all proceeds of which went to the church's youth fund “so these kids won't be hanging around on the streets like sick little chickens.” She had just returned from an appearance on Bing Crosby's television program, which may have added to her fatigue. “Oh, no,” she said, “it's just that California is too far away for everyone.” She had traveled from Chicago, where she had lived since the late 1920s. At 46, Miss Jackson had done her share of physical labor since arriving in Chicago—as a laundress, factory day laborer, and housekeeper.

What about the beauty salon? “Oh, I couldn't work there until I was on my back,” she said, “in 1943.” When did she sing? “Sundays and evenings,” she said. "Prof. Thompson from Greater Salem Baptist Church picked me out of the choir. I sang so loud that I could be heard above everyone else. Do you remember? There were no microphones in churches back then. I just kept singing, and with the Lord's help, the people in the back rows could hear me. I got that from David in the Bible. Do you remember what he said? ‘Sing to the Lord with a joyful voice.’ I followed his advice.

When did I start singing? You might as well ask me when I learned to walk and talk. In New Orleans, where I lived as a child, I remember singing while scrubbing the floors. It made the work go faster. When the old folks weren't home, I'd put on a Bessie Smith record. And play it over and over again. ‘Careless Love’ was what she sang.

Suddenly her eyes sparkled, and she added, “That was before I was saved. The blues is good, but I don't sing it. Remember what I said about listening to Bessie and imitating her when I was a little girl: just remember, that was before I was saved.”

"I played that record over and over, and Bessie's voice sounded so full and round. And I made my mouth do the same thing. And before you knew it, all the people were standing at the door listening.

I didn't know what it was then. I just know it grabbed me. It gave me the same feeling I got when I heard the men outside singing as they laid the railroad ties. I liked the way Bessie shaped her notes."

What was so special about Bessie? Mahalia blinked thoughtfully and said, "When you hear a Bessie song, it almost fits into your own world. You have a restless spirit, you can feel it in her. She's a suppressed woman, a restless woman. She's trying to free herself from something. It's like a sermon, even if it's the blues. More than words, you feel a restless heart.

When I was a little girl, I felt like she had problems like me. That's why it was such a hit with people in the South, because she expressed something they couldn't put into words.All you could hear was Bessie. The houses were thin; the phonographs were loud. You could hear her across several houses."

Before she was rescued, did she come up with the idea of singing the blues? Mahalia laughed. “My father's people were theater people,” she said. "They worked with Ma Rainey and Bessie and the other great blues singers. They wanted me to travel with them. But my mother's people were very religious. They forbade her. My grandmother was also very religious. They told her I couldn't make that kind of money back then. But she said no. And she wanted to have a restaurant. It's easy to be independent when you have money. But being independent when you don't have a penny to your name, that's the Lord's test.

Sure, someone always comes up to me and tells me that if I sang the blues, they'd have all the money in the world for me. Or if I sang in a nightclub, I could set my own price. They don't serve drinks while I sing, and all that nonsense.

They just don't get it. I try to explain. I don't want to hurt their feelings: they don't mean any harm. But it just wouldn't feel right for me to sing that kind of music. After all, I've been saved. The good Lord has helped me in so many ways, and I can't let him down. I was spared. Remember?“

A few years ago, Mahalia lay sick and emaciated in a bed at Billings Memorial Hospital in Chicago. It appeared to be an extremely critical illness that was affecting her chest and, with it, the power of her voice. She attributes her survival and the fact that she is now singing—with the same power as ever—to ”God's amazing grace."

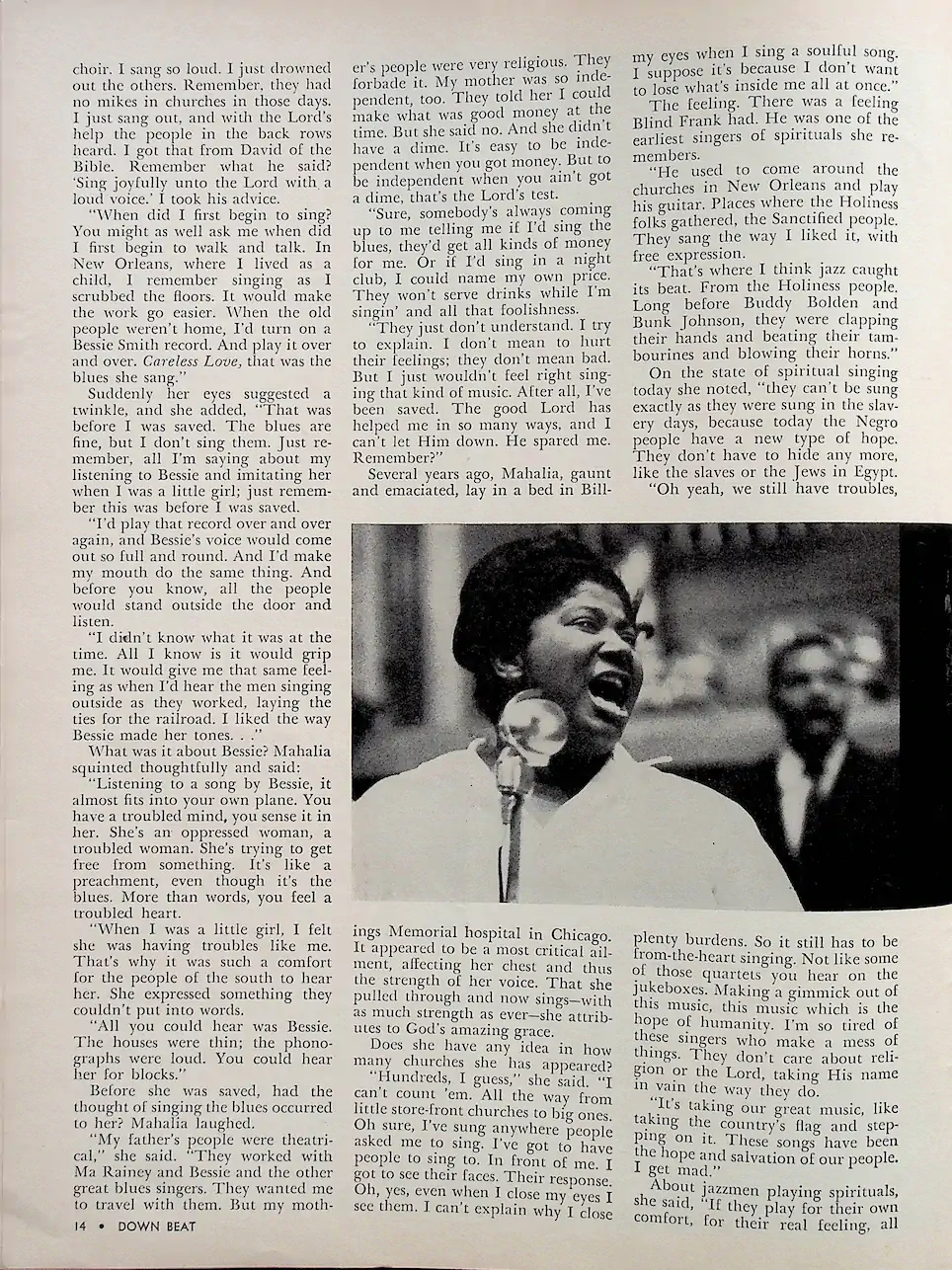

Does she have any idea how many churches she has performed in? “Hundreds, I guess,” she said. "I can't count them. From small storefront churches to the big ones. Oh yes, I've sung everywhere people have asked me to sing. I need to have people I can sing to. In front of me. I need to see their faces. Their reaction. Oh yes, even when I close my eyes, I see them. I can't explain why I close my eyes when I sing a soulful song. I suppose it's because I don't want to lose everything that's inside me all at once."

The feeling. Blind Frank had that feeling. He was one of the first singers of spirituals to revive them. “He always came to the churches in New Orleans and played his guitar. In places where the Holiness people gathered, the ‘Sanctifiée’! people. They sang the way I liked, with free expression. That's where jazz got its beat, in my opinion. From the Holiness people. Long before Buddy Bolden and Bunk Johnson, they were clapping their hands and beating their tam-tams and blowing their horns.“

On the state of spiritual singing today, she said, ”You can't sing exactly the way they sang in the days of slavery because Black people today have a new sense of hope. They don't have to sing like the slaves or the Jews in Egypt.

Oh yes, we still have problems. Many burdens. That's why it still has to be sung from the heart. Not like some of those quartets you hear on the jukeboxes. This music, this music that is the hope of humanity. I'm so tired of these singers who mess everything up. They don't care about religion or the Lord, they take his name in vain.

They take our great music, take the flag of the country and trample on it. These songs were the hope and salvation of our people. It makes me angry.“ About jazz musicians who play spirituals, she said: ”If they play for their own comfort, for their true feelings, then everything is fine. But if they cheat, they are no better than those show-off jukebox singers."

Mahalia stood up and imitated a bloodless soprano, which for a moment was a wildly comical interpretation. But then she became serious again and turned to classical music: "When it comes to singing an oratorio, that's something else entirely. Like the Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah. But for that you need the right voices, good, strong young voices. When I first came to Chicago, our older people sang oratorios in churches. They seemed uncomfortable. I know they felt much more at ease with spirituals or gospel songs or just hymns. They seemed so stiff, not free.

No matter what songs people sing, it has to come naturally to them. They shouldn't just try to sing something because they feel it's the right thing to do. Otherwise, the real person gets lost. They're far removed from their roots.“

A pause. Any thoughts on modern jazz? ”I prefer to listen to the old style because I'm used to it," she replied. "I don't know where jazz is going today. Maybe I'm wrong, but I think they've strayed too far from their roots.

When I was little and they played jazz, the houses just spoke, the music spoke. Some of the progressive jazz sounds to me like lost little children who don't know where they are on the street or what they're doing or why they're doing it. Maybe they're reaching for something good, but I just don't get it.

Today, so many people call gospel songs ‘jazz’. They don't know, they just don't have a clue. Just as spirituals came out of slavery, gospel songs came out of liberation. The jubilee songs that emerged after the Civil War evolved into what we now call gospel songs. ‘Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen’ or ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’. Those are spirituals. ‘What a Friend I Have in Jesus’ or ‘I'm So Glad Jesus Lifted Me’. Those are gospel songs."

The sparkle reappeared. “You know the Fisk University choir,” she said. "They made many of these songs popular. They took the rhythm that the Holiness people gave them and developed it further. They made them concert-ready and embellished them. Not much feeling, but, oh, it sounded so sweet!

‘Take Hold My Hand’ (a piece by Thomas A. Dorsey, America's most prolific gospel songwriter, formerly known as Georgia Tom, who often accompanied Ma Rainey). He wrote this out of his distress and suffering. He was sick, his children were sick; he felt like everything was over. You can sing it as sadly as Bessie. Then I hear a girl sing it and she sounds like Lily Pons. I told Mr. Dorsey how operatic she sounded. My goodness, that's pretty, I wish I could be that operatic."There was a change in the tempo and tone of the conversation, which, like her songs, was sometimes gentle and deeply moving, and at other times earthy and exuberant. She offered random observations about people, places, and things, about what she had lost and gained.Billie Holiday: “I never knew her, never met her, never found out what made her do what she did. But when I saw her last year on the CBS show ”The Sound of Jazz" — you know Lively Arts is serious, right? —I caught that cry from her. I know everyone who saw that show got something from her. She looked like she knew what hardship was. She sounded like it, too."Miss Jackson has a strong connection to Europe, where she was appreciated and accepted long before white people in America. Why did Europeans seem to appreciate her so easily and quickly? “People are people all over the world,” she said, “and anyone can suffer when you sing a spiritual. We all carry different kinds of burdens, and everyone interprets the spiritual in their own way. It's about more than just the words. It's the feeling. It lingers long after the song is over.”

What will tomorrow bring? “I hope that one day I can teach people to sing songs with the deep feeling they once had,” she said. "We shouldn't forget our roots, our history. Sometimes I hear how music should be sung; there are certain notes I want to hit.

I go to my pianist, Mildred Falls. We write it down. That way I can capture the voice inside me. Oh, you should learn, of course. But you should also listen to what's inside you. You have to sing for yourself first. Once you've found that peace within yourself, then you can go to the others. If I do nothing else, I hope to teach people that. Everyone has to find their own way."Mahalia Jackson found her way. She found it long before “Move on up a Little Higher” sold a million copies. In the mid-1940s. There were adversities and detours.

But Mahalia always found her own way to the main road. She will never lose her way.

Author, critic, actor, philosopher, Studs Terkel is as much a part of Chicago as the Marchandise Mart. He hosted two shows on FM station WFMT in this city, performs in various local theater productions, and is currently finishing a screenplay. He was a critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, has worked in radio and television, and is a keen observer of jazz and folk music. His book Giants of Jazz was published by Thomas J. Crowell in 1957.

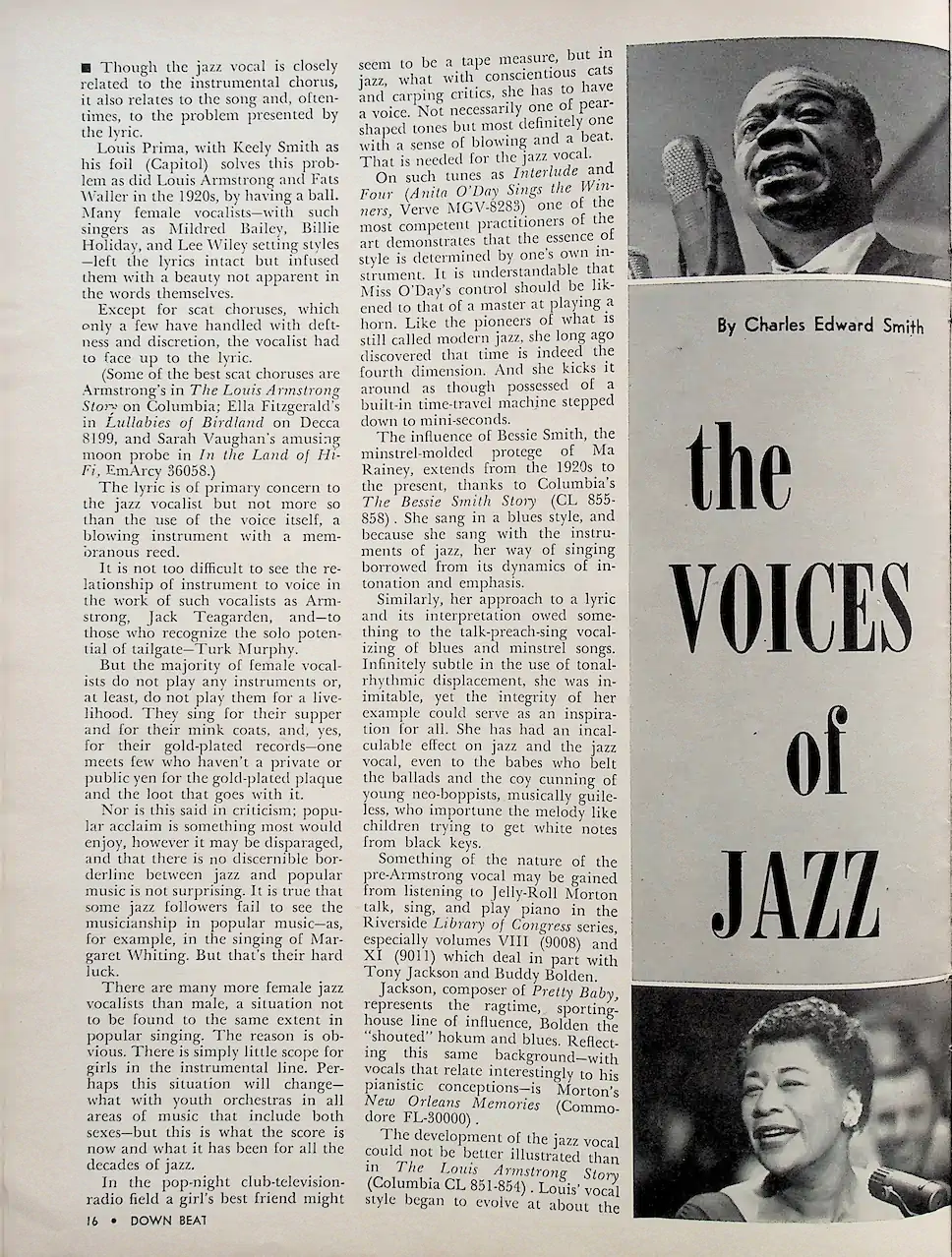

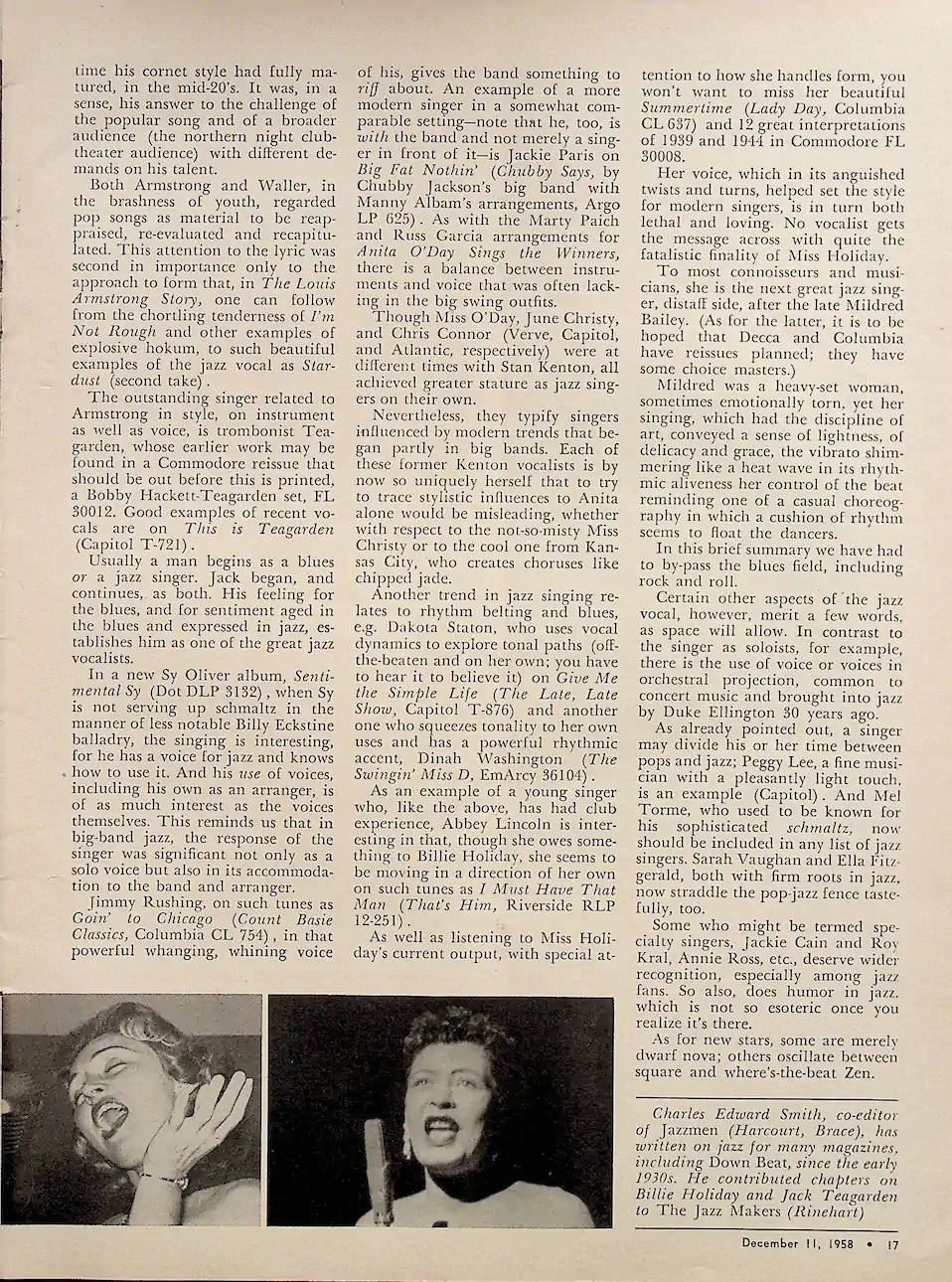

Although jazz singing is closely related to instrumental choir, it is also connected to song and often to the problem posed by the lyrics. Louis Prima, with Keely Smith as his counterpart (Capitol), solves this problem like Louis Armstrong and Fats Waller did in the 1920s by using a ball. Many singers—including singers such as Mildred Bailey, Billie Holiday, and Lee Wiley, who shaped styles—left the lyrics unchanged but added a beauty that is not apparent in the words themselves.

With the exception of chorales, which few mastered with skill and discretion, the singer had to face the lyrics. (The best scat choruses are Armstrong's in The Louis Armstrong Story on Columbia; Ella Fitzgerald's in Lullabies of Birdland on Decca 8199; and Sarah Vaughan's amusing moon probe in In the Land of Hi-Fi, EmArcy 36058.)

The lyrics are of paramount importance to the jazz singer, but no more so than the use of the voice itself, a wind instrument with a membranous reed. It is not too difficult to recognize the kinship between instrument and voice in the works of singers such as Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, and—for those who appreciate the solo potential of Tailgate—Turk Murphy.But the majority of singers do not play instruments, or at least not for a living. They sing for their dinner and for their mink coats and, yes, for their gold-plated records—you meet few who have no private or public desire for the gold-plated plaque and the spoils that go with it.This is not meant as a criticism; popular music is something to be enjoyed, however much one may despise it, and there is no discernible boundary between jazz and popular music, which is not surprising. It is true that some jazz fans despise the musicality in pop music – as in the singing of Margaret Whiting, for example. But that's their loss.

There are many more female jazz singers than male ones, a situation that is mirrored in popular singing. The reason for this is obvious. There is simply little room for girls in instrumental music, unlike youth orchestras in all areas of music, which accept both sexes—but that's the score and how it's been in jazz for decades.

In the world of pop, nightclubs, television, and radio, a girl's best friend might be a tape measure, but in jazz, with conscientious musicians and nitpicking critics, she has to have a voice. Not necessarily one with pear-shaped lips, but definitely one with a feel for phrasing and rhythm. That's what you need for jazz singing.

On tracks like “Interlude” and “Four” (Attila O'Dav Sings the Winners, Verve MGV-8283), one of the most accomplished practitioners of this art shows that the essence of the style is determined by one's own playing on the instrument. It is understandable that Miss O'Day's control is compared to that of a master playing a horn. Like the pioneers of what is still called modern jazz, she discovered long ago that sound is indeed the fourth dimension. And she lets it flow as if she had a built-in time machine set to miniseconds.

The influence of Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey's protégé shaped by the minstrel system, extends from the 1920s to the present day, thanks to Columbia's The Bessie Smith Story (CL 855-858). She sang in the blues style, and because she sang with jazz instruments, her phrasing was reminiscent of the dynamics, intonation, and emphasis of jazz.

Likewise, her approach to lyrics and their interpretation was somewhat reminiscent of the talk-preach-sing vocal technique of blues and minstrel songs. Infinitely subtle in her use of pitch shifts and rhythmic shifts, she was inimitable, but the integrity of her role model could serve as inspiration for all. She had an invaluable influence on jazz and jazz singing, even for the little ones who sing ballads and the young neo-boppists who are less musically sophisticated, who rush the melody like children trying to get white notes out of black keys.Something of the nature of the vocal style before Armstrong can be heard when listening to Jell-Roll Morton on the Riverside Library of Congress series, particularly volumes VIII (9008) and XI (9011), which deal in part with Tony Jackson and Buddy Bolden.

Jackson, composer of “Pretty Baby,” represents the influence of ragtime and the sport house influence, while Bolden represents the “shouted” hokum and blues. Against this backdrop—with vocals that harmonize interestingly with his pianistic ideas—Morton's New Orleans Memories (Commodore FL-30000) is reflected. The development of jazz singing could not be better illustrated than in The Louis Armstrong Story (Columbia CL 851-854). Louis' singing style began to develop at about the same time as his instrumental playing.

© downbeat 1958