The Rise and Fall of Coronet

Glitz, glamour, and education

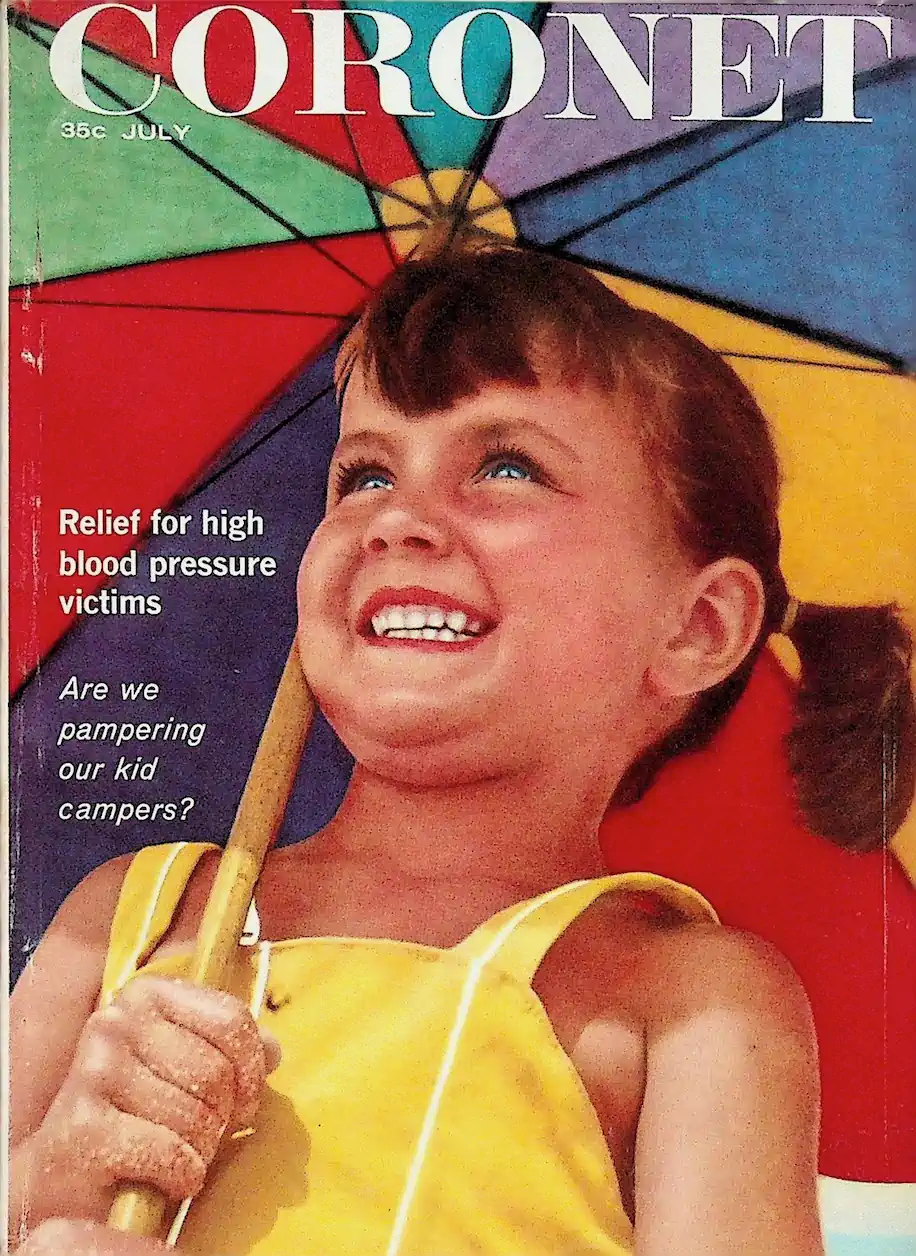

At a time when television was still in its infancy and the internet was science fiction, a small pocket-sized magazine ruled American living rooms: Coronet. It was more than just a magazine; it was a window to the world, a teacher of etiquette, and an art gallery for the masses.

The "pocket magazine" for the modern mind

Founded in 1936 by David A. Smart—the mastermind behind the legendary Esquire—Coronet pursued a bold goal. While its major rival Reader's Digest focused primarily on text and condensation, Coronet brought aesthetics into play.

With a mix of high-quality photography, literary essays, and practical life advice, it struck a chord with the spirit of the times. At its peak in the 1950s, over three million people leafed through its compact pages every month. Anyone who read Coronet was considered informed, cultured, and in tune with the pulse of society.

More than just paper: The era of "social guidance"

However, what made Coronet immortal was not only the magazine itself, but its offshoot: Coronet Films. After World War II, the publisher flooded American classrooms with 16mm educational films. Generations of students learned from Coronet how to behave on a date, why to brush their teeth, and how to recognize "communist infiltration." These films shaped the image of the "perfect" American suburban idyll of the 1950s—an image that today often oscillates between nostalgia and ironic criticism.

The end of an institution

But the success was short-lived. In the 1960s, the zeitgeist changed radically. Television took over the role of visual storyteller, and advertising customers migrated away. In 1971, after almost 300 issues, it was over. The magazine that once promised to offer "the best of all worlds" could no longer keep up with the speed of the new media world.

Today, Coronet is a sought-after collector's item. It serves as a fascinating archive of an era when people believed that the world could still be explained in a handy paperback.

When Mahalia Jackson enchanted Coronet

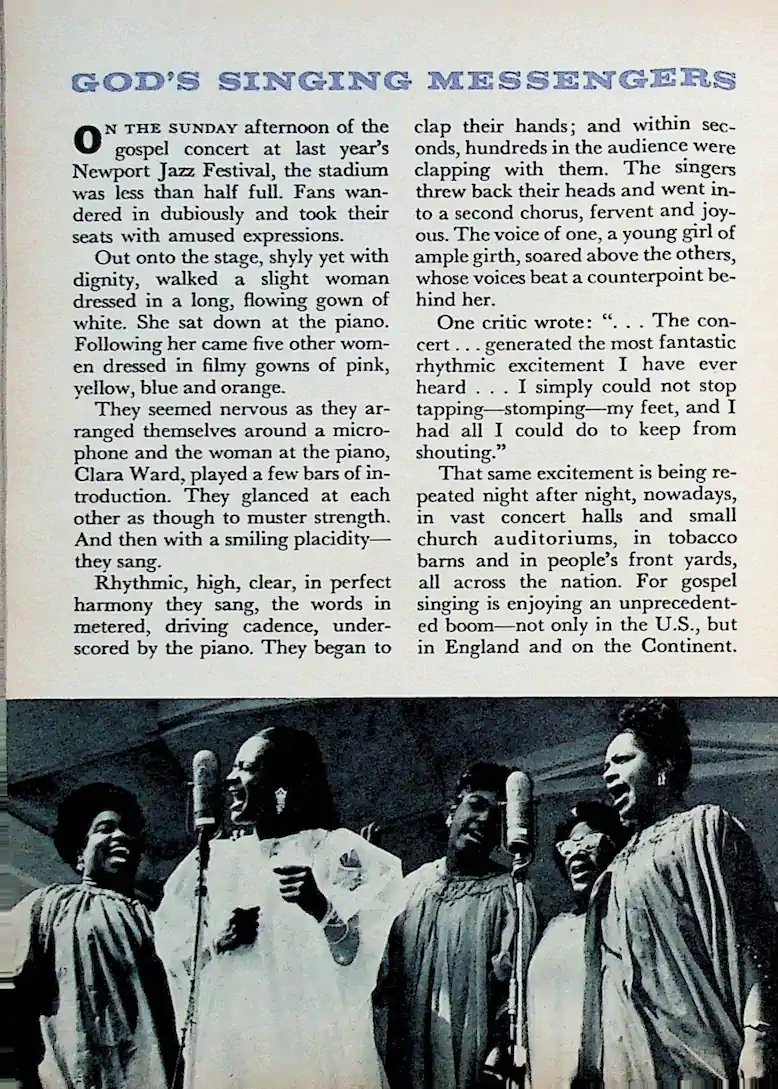

It was 1958 when gospel legend Mahalia Jackson finally made her mark on American pop culture. Coronet magazine, always on the lookout for inspiring stories with depth, dedicated an impressive feature to her and the emerging gospel phenomenon entitled "God's Singing Messengers."

A spiritual "gold rush"

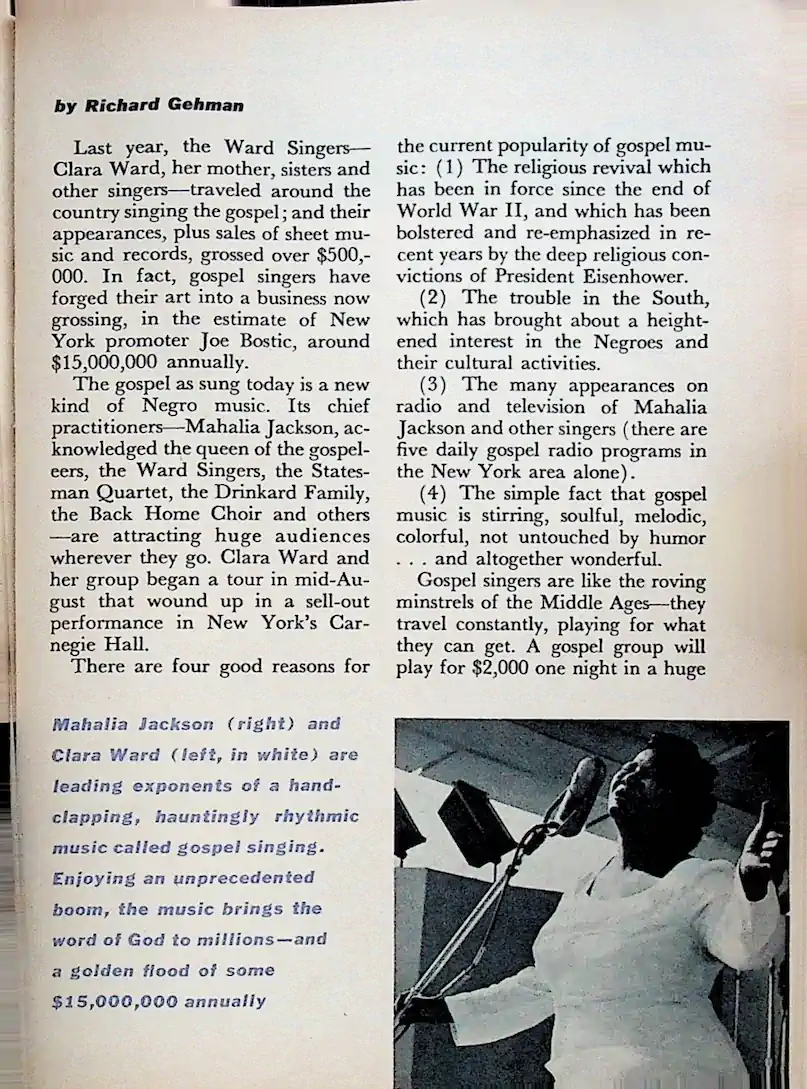

The article highlighted a fascinating paradox of the late 1950s: while music remained deeply religious, it suddenly became a huge business. Coronet reported with awe on the $15 million that gospel music was generating annually at the time—an astronomical sum for the era. Amid this "golden flood," Mahalia Jackson stood as an unshakable rock. The magazine portrayed her not only as a singer, but as a moral authority who brought the word of God to millions without betraying her roots.

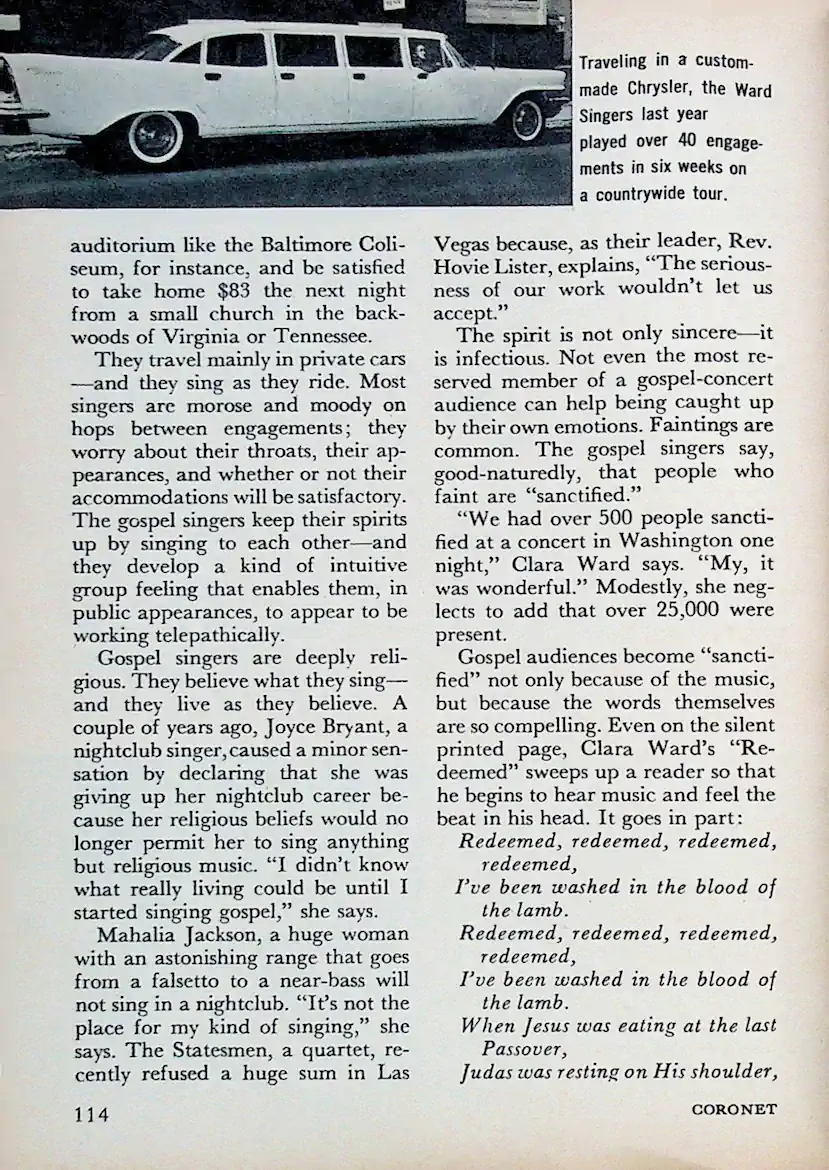

The visual presentation was typical of Coronet's style. The article was not a dry interview, but a five-page "picture story." Readers saw:

Close-up shots

The ecstatic devotion on Jackson's face during their performances.

In contrast

In addition to Jackson's simple spirituality, the magazine also showed the more glamorous side of the scene, such as the Clara Ward Singers' custom-made Chrysler automobile.

Emotions

Coronet's characteristic "hand-clapping" and "haunting rhythms" were described so vividly that you could almost feel the rhythm rising from the page.

Why 1958 in particular?

The article appeared at a time of great change. Mahalia Jackson had just moved audiences to tears at the Newport Jazz Festival and appeared in the film St. Louis Blues. For Coronet's predominantly white readership, she was the bridge to a culture full of power, hope, and dignity—values that the magazine cherished above all else. A piece of contemporary history: this article from 1958 is now a valuable document of how gospel music conquered the mainstream and crowned Mahalia Jackson the "Queen of Gospel."

© Coronet 1958