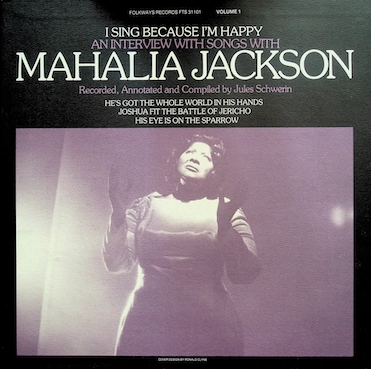

An interview with songs with Mahalia Jackson

Recorded, annotated, and compiled by Jules Schwerin

© 1979 by Folkways Records & Service Corp., 43 W. 61st St., NYC, USA 10023

Album Nr. FTS 31101/31102

Background

This edition of the album "I sing because I'm happy" is available on vinyl LP and CD. The vinyl LP includes the interview in printed form, as well as an introductory text by Jules Schwerin. The interview has been supplemented with several songs by Mahalia: "He's Got the Whole World in His Hands," "Joshua Fit to Stand," and "His Eye Is on the Sparrow."

Jules Schwerin's introduction to this interview offers a fascinating insight into the social and cultural dynamics of the United States in the mid-20th century, particularly in the context of the African American experience. The text highlights several key themes:

Artistic inspiration and intercultural encounters

Schwerin's initial search for a film idea leads him to a Mahalia Jackson concert, which is a "stirring revelation" for him as a white filmmaker. This illustrates the transformative power of art and music across cultural and racial boundaries. The description of Mahalia Jackson's performance—her hip movements, hand clapping, the energy of a "golden blend of religion and theater"—underscores the deep roots of gospel in African American culture as an expression of joie de vivre, spirituality, and resilience.

Overcoming racial barriers and building trust

The "getting to know each other" phase between Schwerin and Jackson, described as a process of "stripping away our facades of racist behavior," is crucial. It illustrates the challenges of interracial communication and cooperation in a society marked by segregation. Jackson's initial skepticism toward a recording device and a "strange, white person" is understandable and reflects the deep-rooted mistrust that results from structural racism. The gradual development of "mutual trust" is an important aspect that was essential to the authenticity of the planned film project.

Mahalia Jackson as a contemporary witness and cultural icon

Mahalia Jackson's recorded memories are a valuable treasure trove of oral history. Her accounts of the "degrading life of the segregated black population" in New Orleans, the cruelty of Mardi Gras from an African American perspective, and the origins of her singing style offer an authentic perspective on the reality of the Jim Crow South. Her steadfast refusal to sing jazz or blues—despite financial enticements—underscores her deep conviction and belief in the uplifting message of gospel music. She positions gospel not only as music, but as an expression of "hope" and "God's love," cementing her role as a spiritual leader and artist.

Racism and segregation as obstacles

The text documents the pervasive discrimination. The anecdote about Mahalia's arrest by a police officer in Louisiana, which resulted in an arbitrary fine, is a striking example of the systematic harassment and disenfranchisement of Black people. Schwerin's inability to invite Jackson to "famous restaurants" or introduce her to his "envious white friends" illustrates the deep-rooted segregation that was still indirectly palpable even in the North. This highlights how racism not only hindered individual actions, but also social interactions and the realization of projects.

The commercialization of art and cultural stereotypes

The failure of the original film project due to lack of funding is symptomatic of the low esteem in which African American art forms were held on the commercial market at the time. Investors saw "no commercial future" for gospel music, reflecting white dominance and the lack of recognition of black culture in the entertainment industry. The "irony" of Jackson's later meteoric rise and her acceptance of the "lucrative but stereotypical 'Darky' role" in "Imitation of Life" highlights the pressure to conform to prevailing stereotypes in order to achieve commercial mainstream success. Schwerin's observation that television producers lit her face "without proper shadows" or sat her in an "old rocking chair with a scarf or bandana on her head" reveals the subtle but effective mechanisms of maintaining racist images in the media.

The legacy of Mahalia Jackson and the civil rights movement

The addendum emphasizes Mahalia Jackson's immense importance not only as an artist but also as a symbolic figure of the civil rights movement. The huge turnout at her funeral and the words of Coretta Scott King ("black, proud, and beautiful") and Jesse Jackson underscore her status as an icon of the struggle for equality. Her influence went beyond music; she was a voice of hope and resistance during a time of profound social change in the United States.

Overall, Schwerin's text offers a multifaceted reflection on art, racism, cultural identity, and the challenges of media production in the context of mid-20th century American society. He underscores the importance of Mahalia Jackson as a key figure whose life and art reflected the complex realities of her time.

©Thilo Plaesser

The INTERVIEW - Mahalia Jackson recounts

The interview was recorded in 1958.

When I was a little girl in New Orleans, we lived on the levee, and the levee wasn't far from the railroad tracks, and the levee bordered the Mississippi River. And there used to be people who lived there, and they used to fish there. I was born on Water Street, about a mile from my parents' house. And out on Water Street, Water and Audubon, Audubon Street, there used to be a ferry that took people back and forth across the river to Weswego, which is well known, another small part than Algase, Algase, Louisiana, but they called it Weswego. And the men worked out there on the riverbank. Big ships used to come and bring bananas and various other things. And there was a big coal yard. As far as I know, it all belonged to a wealthy family named [name not mentioned in original]. They owned this ferry and the coal yard. Even part of the public belt railway that used to transport the cars on the tracks around the sugar refinery where they used to grow sugar cane, and not far from where they used to grow rice. Now they owned this ferry and all the work at that time down in the community, in this community where the Negroes worked. They used to be in Audubon and out by the river, out by the dock. This big place where people worked, there was gambling and everything was there. And not far from there was the whiskey distillery, and about half a mile further on there was another place where Negroes worked. And later, where I grew up, there was the government fleet, where many Negroes worked. And there were boats that went up and down the Mississippi. I never really knew what went on there, except that Negroes worked there.

I also remember that there were some men who worked on the public railway. We called them "Hot Lips," and they were train drivers. They were switchmen and train drivers who worked on this train and were very nice to us children. They often took us with them on the train or in the freight cars. The freight car was the last part of the train. And sometimes they put us in the first part of the train and took us kids to the sugar cane fields. They often gave us something to eat. And that train still runs, and the tracks are still the same.

Back when I was a girl, the houses were pretty run-down, and many of them still are. And the rent was no more than about six or eight dollars a month. And times were pretty lean. I don't know, I was born into those circumstances, but it was a sad feeling because there weren't many of us who lived particularly well. But I felt that I could live better. And I dreamed of living better, but circumstances often took me to the levee, on the other side of the levee near the Mississippi River, down by the riverbank, and I would collect wood, and my people were poor and I had to collect this wood, which would then float out on the river onto the sandbanks on the shore, and I would let it dry and bring it home so that we had wood for cooking and heating to keep us warm in the winter.

And I find myself wandering around this river, in front of the river, because I don't know, it seemed like I could think better there. I've always been a child who thought that way—into the distant future—I didn't know what it had in store for me, but I would find out there on the Mississippi. I could think better there. I often took an axe with me to where old barges lay around and chopped wood. It was nothing unusual for a girl to chop wood or do things like that, or perhaps cut down a tree to get kindling for the home. But I found a certain pleasure in doing it to keep myself busy—otherwise I would have been sad because of the circumstances.

You could be inside the house and see the sun outside. When it rained, it rained inside too, and that made me very sad all the time. And the only way to get coal was to walk a mile away and pick up coal on the railroad tracks and carry it home, sometimes on your back or on your head, so that we might have enough coal for the winter to keep the house warm.

From the meager wages their mothers earned or their fathers would work for on the government fleet or on the railroad tracks to – some of them may have worked as dockworkers. Well, the men who worked as dockworkers, that was on the riverbank, they earned a little better. But there were only a few Negroes who worked as plasterers or bricklayers in New Orleans, but the people fed their families on the low wages – many of them grew their own vegetables. And so we often went to the riverbank and caught our own fish, crabs, and lobsters. And we could often eat whatever we wanted because we were near the river and could catch these foods, so we ate pretty well because we lived near the riverbank. And those who lived downtown in the French Quarter and other parts didn't live quite as well. They might have had to get their food at the market if they didn't go fishing.

And most of us children walked to school along 24th Street, parallel to the railroad tracks. The children came from different parts of the city to attend school. And we walked up there and were able to attend—this school only went up to ninth grade at the time, one year of high school. I didn't go very far to school, but I grew up in a very strict family that kept a close eye on me, and I had to be secretary for all the charitable organizations, which kept me away from many other young people. That's why I was always more mature than other young people. That's why I always had this sad feeling because I had to be with old people to act as secretary, and of course that made me a little more profound than most other children.

I can't remember many professional people. The only working person I knew at the time was the daughter of the teacher Mr. Sam Williams, who taught at the school on 24th Street where I went to school, and many of the teachers there, Miss Green and Miss Mitchell, knew me. The next professional was Dr. Gaines, and he was a great doctor, but otherwise the next profession for black people was a hairdresser, maybe he had a barbershop, maybe they had a small restaurant, and maybe a seamstress or something like that. But most people worked for white people, where they worked in the yard for a day or they washed and ironed in white people's houses, where the children went to the white people to get the clothes off their heads or off their shoulders and bring them home. Many of them had to skip school to help their families with this work, which paid no more than maybe 75 cents a bundle or a dollar and a half. And you would see many children with these baskets full of ironed clothes that they were taking back to the white people who might live on the Avenue or Broadway in the better parts of town. And then many of the Negroes were maids or cooks. That's how they earned their living. You might hear a man coming down the street selling bananas, in a very sad tone, a very sad song about vegetables, a very sad song. "Vegetables today, bananas today" or something like that. That's how people in New Orleans earned their living. There were no shops like the Negroes have today. The shops that were around back then were very poor.

You know, New Orleans is a city where people believe in living for today and are happy. It's a very cheerful city. They believe in enjoying life to the fullest, and as poor as they are, they have these good times. In New Orleans, it was customary to work—when they finished work on Friday, they started to rest until Blue Monday came. Blue Monday is known for being a day when no one worked, but just had a good time and they... There are a lot of people out there who never cared about getting rich, they believe in enjoying life. And that was a wonderful part of life in New Orleans to see. Even though people had nothing, they had a wonderful attitude despite the racial segregation that existed there, because the Negroes kept to themselves. They created their own joy and still had their own tragedies and problems there. But somehow they managed to keep going.

Where people used to meet and dance, where we listened to Dixieland music, as it is called today, but back then we just called it "music." They called it jazz. This type of music was despised by the upper classes at the time because they considered it "immoral music." Music for the common people and in the dive bars, in the saloons, the music that the world raves about today. I knew jazz music inside and out. I didn't know King Oliver that well because he was a much older man, but I heard him playing on trucks when they played at the Bulls Club downtown or in the backyard. I heard them driving around promoting this kind of music. These kinds of people weren't even on records. I heard them playing before the world even recorded them. I heard them before Louie Armstrong left and came to Chicago.

Papa and King Oliver and all those people, I saw them. And Bunk Johnson. They were around because in the different parts of the neighborhood where we kids had to go to school, we could hear old people talking about such things. We kids weren't allowed to go, but we could hear it. And we heard jazz being played when I was a kid, before it was recognized. Many of these men didn't have a specific place to play, no more than, as I said. Only at dances or small lawn parties. New Orleans was known for its beautiful lawn parties, which had been started by people of color. There were beautiful lights, Chinese lights, and sawdust, and they danced on the ground. They threw the sawdust in the air and played three or four jazz pieces and had a lot of fun until late at night and enjoyed themselves.

Many of the songs you hear today that come from New Orleans, such as "When The Saints Go Marching In" and "When We Gather At The River," date back to this period, and many of these musicians come here to play this type of music because New Orleans is known for its large, pompous funerals. When someone from the community who was very popular or belonged to secret societies such as the "Knights of Phythlans" or similar groups died, a band was always hired. This proves once again the joie de vivre of the people of New Orleans, who cried when a child was born and rejoiced when it died. And they held big funerals.

In the early days, when I was a girl, they were pulled by two white horses, or maybe four white horses, with the knights of Phythlans in their uniforms, which was a magnificent spectacle. But at the funeral, there was a band if it was a man. If it was a woman, they didn't usually do that for women, but if a man had died, there was a band. When the body was carried out of the church, the drums played sad songs like "Nearer My God To Thee" and "What A Friend We Have In Jesus." And they marched behind the hearse carrying the deceased all the way back to Green Street Cemetery or another cemetery in the parish, near the parish.

After the funeral of the deceased, this band began to play religious songs, and people from all over the area gathered at the cemetery and came back and danced to the music in the streets. When "The Saints Go Marching In" or whatever they wanted to play was played. The children and old people came back from the cemetery to the streets, on bicycles, trucks, or whatever, and were infected by the exuberant mood of this jazz music. And that's why many of the songs I sing today have this rhythm, because it's a legacy, things I've done, things I grew up with, and things that happened in New Orleans. And when I came up north, a lot of people asked me about the style—the way I sing these religious songs. But I've heard them sung that way since I was a child. That's probably why many people think that a lot of the songs I sing sound jazzy, because jazz musicians played them, but it was something I heard as a little girl and still hear today.

The kind of music I'm talking about was dedicated to all the people in New Orleans after they buried their dead, as a second line, that's what a second line is. And a lot of the white people and people who didn't go to the cemetery would stand on the street. It always caught their attention. People were always happy. They knew someone had died, but this music did something to them. And this kind of music is really in my soul. It's just that this kind of music is like—what is this great song that the Italians and the Irish love so much? Every country has its own folk songs. Well, that way of singing and that way of doing things is just the old days, that's me. It's part of the people of New Orleans, that's just the way people live there. It's like eating red beans and rice.

In my hometown, where I grew up, there were many things I didn't like. There were many things I dreamed of as a child, things I wanted to be—like a teacher at school, a nurse, or a doctor. I always wanted to be one of them. For example, I didn't like Mardi Gras in New Orleans. To me, it was always a terrible sight. I saw so many people get hurt on that day. It was a beautiful sight, but what was going on there made it terrible. People spent all their money. They saved all their money from one year to the next so they could dress up like the beautiful Indians. As if they were chiefs of the Zulu tribe in Africa. And many of the women would wear expensive dresses. And all those beautiful dresses and their gorgeous appearance would cause many of them never to return home because they would be killed. Because on that day in New Orleans, people could cover their faces freely, and for all the crimes that were committed, there were never any charges.

And there were different Indian tribes fighting each other on that particular day. There were the reds, the whites, and the blues, the yellow Pocahontas, and many others that I forgot as a child from various wars. Like the 12th war in New Orleans, far behind the city, where different people had organizations, and these men were chiefs of certain tribes who came together on Carnival Day. This went on for a whole week.

The white people had their big parade floats on Canal Street, which were very beautiful and very tall. Everyone came from different parts of the city, different neighborhoods, to see the queen riding on these beautiful floats. They spent millions of dollars. People from all over the world came to New Orleans to see it. But it seemed like such a tragedy for my people because they had something going on between the Indians, who were called tribes, these Indians. And they had Little Eagles, I think it was Boy Blue, another Indian name that I can't remember right now. And if one tribe demanded that the other fly low on that day, and if they didn't, they would kill each other, and nothing would happen because it was an organization that everyone had to join and submit to that kind of thing. And the state—the law never did anything about it. And I hated that and didn't like Mardi Gras because of that kind of thing. They would be free to shoot and kill each other.

There is another side to this story that is quite sad: some of the colored boys who hung around the saloons and didn't go to church, maybe went to the pub and played pool. Whatever they did, I don't know, but I do know that there was a very bad police system there that was harsh. They would arrest the colored people just for standing in their own community. They were arrested and put in jail. Many of them were put in jail and many of them were badly beaten, and many were killed, even if they had resisted a police officer. Those were the sad events that many of the mothers there, who were quite sad, experienced. There were only certain places where Negroes were allowed to go. And whenever we heard that Negroes were having trouble with each other and the police were coming, it always ended badly because it wasn't enough for them to fight among themselves; maybe the police beat them because they considered them bad Negroes and so on. Then he might have killed one of them because he would claim that the Negro had tried to attack him or something like that. And these things made us feel that we had no protection.

I didn't know a single black lawyer in New Orleans. If he went to jail and wasn't well regarded by certain white people, he was treated pretty badly. That was the sad thing about it, we were always afraid of trouble in the neighborhood if one of the boys got into trouble or something like that, because we knew that when the police came, the Negroes would jump over fences to get out of their way and out of their way so they wouldn't go to jail, and take away the little money their mother or father had scraped together to get them out of jail. Either they would be treated so badly—they would be beaten so badly that the man was a man, and maybe some of the Negroes would have resented the officers for treating them so badly. And they would do it too. When the Negroes saw the police showing up somewhere, they would scatter like flies around the billiard room, which was an automatic pastime where everyone could enjoy their lives. And they would chase them away. The Negroes would have to run as if King Kong were coming toward them when the police arrived. It was a terrible environment, sad for the colored people who lived in that community.

But despite all this, they remained fairly optimistic about life. During the Prohibition era, black people often had houses where they could go to get alcohol or something to drink. The police would come and raid these houses, locking people up in jail or something similar. These people often had children who were ashamed to raise their children. It was the only way for these Negroes to earn a little money, perhaps to help their children go to school. But they broke in without a permit or search warrant and took them all to jail, which was very sad. These people were not bad people, but human beings are known to drink. But at that time, it was against the law to run such speakeasies. Under these circumstances, it often happened that the preacher was the one who had influence and could perhaps get these people out of trouble. Many of them fell back into this activity.

But back then, the preacher was the only voice the Negroes had, the only one who could perhaps go to court and ask the judge for mercy for the people. If a girl went astray and became a bad girl—in the early days, as you all know, there were different parts of the red-light district in New Orleans—the mother would always ask the pastor to try to bring the girl back home and keep her away from the bad houses of New Orleans. Even if the boy became so bad and a delinquent, the parents did the same thing: they might go to the priest if they were Catholic, or to the minister. The minister had really—at that time—lived such a life that people had respect and trust for him, that they could get their children back or get them mercy. Even if they had committed a crime and ended up in prison, leniency would always be shown to the minister in order to place these people in the good hands of this faithful minister.

The only leisure activity we children had was at church. And the church was the center of our lives as children, where we met and played. We sat at the back of the church, which was called the "church hall." We children would meet there and sing and play little games we had made up ourselves. And often, when we weren't there, many of us would sit at the foot of the dike or on some of the railroad ties where the railroad tracks were. There we would build a fire, sit together, and sing songs. Some of them were spiritual songs, others were songs we had heard on some of the old records from earlier times. There was a boy named Clifford. He played the ukulele, and we sang songs, ate pecans, sugar cane, and various other things. We baked sweet potatoes in the ashes we got from the wood. And so we often had fun at home. Since New Orleans is a Catholic city, it starts right after Ash Wednesday. Either it lasts until Ash Wednesday—it's been many years since I've been there, so I've forgotten some of these things—but since it's a Catholic, strongly Catholic city, I think they either start on Ash Wednesday or end on the Wednesday before Easter, before Holy Week begins, before Easter Sunday, until Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday.

When you talk about the church, as beautiful as the city of New Orleans is, it is also a very, very religious city. With all its French Quarters and red-light districts, there were people who were God-fearing and truly believed in raising their children in the fear of God. In the small community where I grew up, it was respected in its quiet way by those who didn't go to church. And it played its role because, as I said, it was the only playground and recreation center for the children. And I always liked the church because of its powerful music and the way the services were conducted. I was drawn back to church again and again. And that was because I liked the songs and I liked the way the old preacher gave his sermons. He wasn't as educated as some of our clergy today, but he had a way of preaching, a singing tone in his voice that sounded sad. And that moved me deeply. That was really the basic way I sing today, because I heard how the preacher preached in a—I mean, he preached in a cry, in a groan, he kind of screamed like he was singing, a groaning tone that pierced my heart.

And when people sang, I always loved the way the congregation sang. It seemed to have a different sound quality than the choir. There used to be some evangelists who came to our church from the South, and there were always a lot of children in our church, and there was always something going on. It was a small church in its own way, but it had a program for young and old people. The pastors didn't make much money back then. They barely got—I think it was a salary of $20 a week. But a pastor had to have another job to make ends meet for his family. Because back then, the church didn't pay the clergy anything. If a man was a man of God, he just lived off what people could give him. If they could give him chickens or other things from their farm. Maybe they bought him a suit once a year. Or maybe someone bought him a pair of shoes. And maybe they didn't even do that. But he had to have the love of God in his heart to be a preacher, because there were no concrete plans to take care of a clergyman completely in those days.

Ich glaube, einige Leute schämten sich ein wenig für Volkslieder und Gospelsongs, weil man dafür keine lange Übung brauchte und es einfache Lieder waren, die aus dem Herzen kamen. Und manchmal dachten die Leute nicht einmal, dass das Kunst war, was man Kunst nennt. Etwas Kompliziertes, das man erst lange studieren musste. Aber etwas, das von Herzen kam, war, denke ich, einfach zu akzeptieren.

No one can hurt the gospel in this way, because I say that the gospel is strong. Like a double-edged sword, strong enough to cut through anything, even if Satan himself sings a gospel song. It's nice to see everyone trying to sing it, because there are some people who make fun of it a little.

These songs are the staff of life. I know someone who sings the blues. But the blues sounds really good, and the blues is part of our great musical heritage. And I wouldn't say it's not our best music, but it doesn't give you any relief. It's like a man who drinks, and when he's sober, he still has his problems.

It depends on what kind of mood I'm in. Songs suit my mood. There are some songs I like to sing: "Jesus Love Of My Soul." I sing that one sometimes for myself. "My Faith Look Up To Thee." "Just As I Am." Sometimes you feel so far away from God. And these deep songs have meaning. It seems like they restore the connection between you and God.

End of interview

Background – a failed film project

Why the movie "Got to Tell It" was not made during Mahalia's lifetime

The planned film collaboration between documentary filmmaker Jules Schwerin and Mahalia Jackson did not come to fruition during their lifetimes. Several factors, ranging from Schwerin's previous experiences as a filmmaker to financial discrepancies and Mahalia Jackson's career path, contributed to the project being put on hold for the time being.

The shadows of the "blacklist" – Schwerin's previous experiences

Jules Schwerin's previous documentary film project, Cannonsville (later renamed Indian Summer), failed commercially due to McCarthy-era blacklisting. Pete Seeger, who composed and performed the film's soundtrack, refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Schwerin, in turn, refused to remove Seeger's name from the film credits. This steadfast stance led to cancellations of screenings and forced Schwerin to store the film copies for years. Although it was not a project about Mahalia Jackson, this experience shaped Schwerin's understanding of the challenges faced by independent filmmakers during this politically tense period.

Financial divide and new horizons

After Schwerin showed Mahalia Jackson his film "Indian Summer" and presented her with the idea for a related drama about black liberation and gospel music, he offered her a down payment of only $200 for the planned short film. Mahalia was visibly dissatisfied and found the amount insulting. She expected a much higher sum, as she apparently equated a small documentary film project with the expectations of a Hollywood production. Her lack of enthusiasm for Schwerin's modest film project became clear when she told him that she had instead received an offer from Universal Pictures for $10,000 a week. This highlighted her changed priorities and the unattractiveness of Schwerin's offer compared to the opportunities available to her in Hollywood.

From film project to book – "Got to Tell It"

In light of these challenges and Jackson's higher priorities, Schwerin decided against making the film at that time. Instead, he shifted his focus and wrote a book about Mahalia Jackson entitled "Got to Tell It."

The late realization - A movie after Mahalia's death

Ironically, a film entitled "Got to Tell It" was finally made – but not until 1975, twenty years after Schwerin's first encounter with Mahalia Jackson. The initiative came from CBS News. The fact that the necessary funds for such a film were only available after Mahalia Jackson's death is often described as a bitter irony of music history. This points to the lack of acceptance and funding for black gospel artists in the mainstream film business at the time, which was limited during Mahalia's lifetime.

Criticism of Schwerin's portrayal

It is important to note that Schwerin's book about Mahalia Jackson, although based on interviews, attracted a lot of criticism. Critics criticized the lack of source citations, a paternalistic tone, and misrepresentations of her life and roles. In particular, his portrayal (he had never seen the film!) of her involvement in the film "Imitation of Life" was criticized. These objections confirm that Schwerin's work, even if it arose from personal fascination, was not always objective or factually accurate.

©Thilo Plaesser