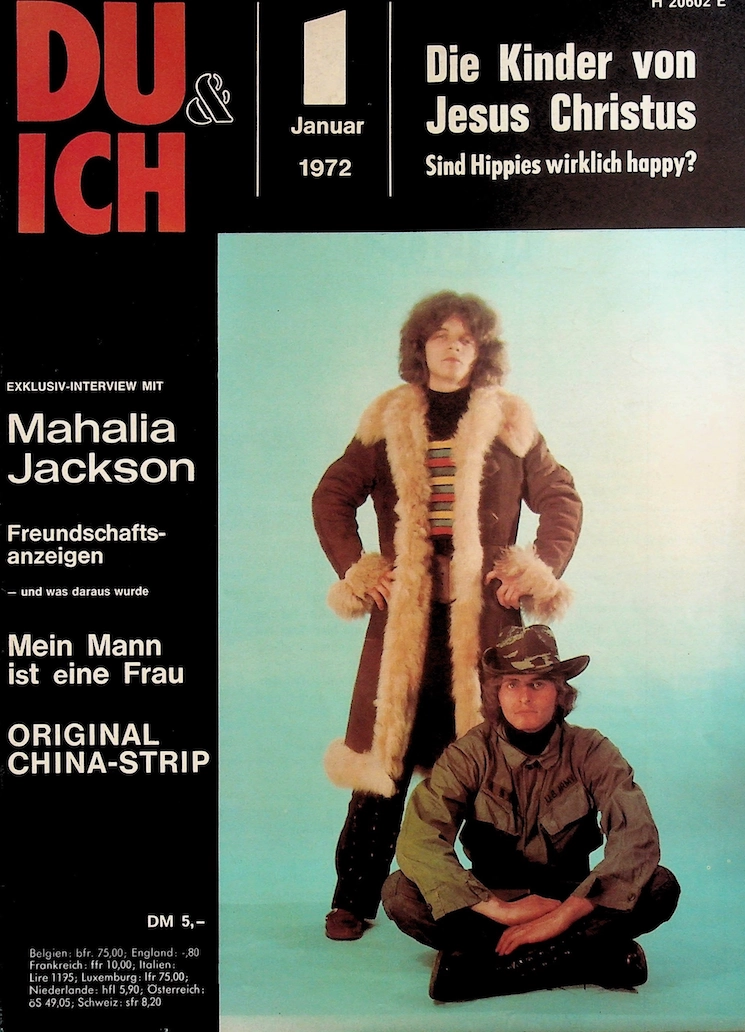

German gay magazine from the 1970s

In the January 1972 issue of the German gay magazine "du&ich," a remarkable interview with Mahalia Jackson appeared, providing a deep insight into her thoughts. Norbert Rank spoke with the world-famous spiritual singer in Berlin for du&ich two days before she had to cancel her European tour due to illness.

The interview appeared in the January 1972 issue.

On January 27, Mahalia died at the age of 60.

The interview

du & ich

Mahalia Jackson, we thank you very much for agreeing to give us fifteen minutes of your time despite your immense press commitments and your current state of health. Just last week, you declined an interview with us, but when we told you more about our magazine, you spontaneously agreed. Usually, it's the other way around: most artists agree to an interview, but later, when they find out what kind of magazine we are, they refuse to talk to us. How do you explain your unusual behavior?

Mahalia Jackson

I am generally very friendly toward the press, but at the moment I lack the energy for such commitments. I have great difficulty getting through my concerts, and even for that I need medical help. That is why I could not have justified answering a few trivial questions for some family magazine. When I heard that you are an organ for a minority, I changed my mind. I myself belong to a minority, and I know that we—whether black or gay—are dependent on every gesture of goodwill. We are also more grateful than the general population.

du & ich

You have been traveling around the world for many years, singing to sold-out venues and giving your all. You could truly afford a quieter life, which would also be better for your health. Is earning money so important to you, or are you so committed to your art that you simply cannot stop performing?

Mahalia Jackson

Money has never meant much to me. For example, I don't even know how much I have. I perform at at least two dozen charity events every year without earning a cent. But I can't, as you say, sit quietly at home. I want to bring joy with my songs, to convey something to the audience: my heart doesn't sing for dollars, but for humanity.

du & ich

Our magazine is planning a large gala event for elderly and needy homosexuals in the near future. Would you be willing to perform at such a charity event free of charge?

Mahalia Jackson

Yes, if you let me know in advance.

du & ich

Aren't you afraid that such an appearance could expose you — from your audience's point of view?

Mahalia Jackson

No. My audience understands me—and I understand my audience. We are one big family. The people who want to hear my songs are well aware of the great injustices in the world and the small injustices of everyday life, and they all want to fight against them, but they are powerless.

du & ich

Do you believe that you can improve the world from the front of the stage?

Mahalia Jackson

No, that would be a bold idea, unrealistic. No singer, no actor, no writer, no pastor, not even a politician can improve the world; it remains as it is and as it always has been. Over the course of thousands of years, humans have changed only in insignificant ways, in outward appearances; their problems have remained the same and will probably remain so.

du & ich

What do you see as your role?

Mahalia Jackson

I want to make my audience happy for two hours, and maybe I'll even manage to make people think — that's a lot and very little at the same time. As an artist, you have to be modest about that.

du & ich

Can you describe your attitude toward homosexuality?

Mahalia Jackson

No. I don't have an opinion on homosexuality. I also don't have an opinion on people who like red roses or who, unlike me, are early risers. But I do have an opinion on people, and I don't care whether they have black, white, or yellow skin; I don't care who they are sexually attracted to or what political or religious beliefs they hold. I hate prejudice. I know from my own experience how painful it can be. People tend to form judgments about others they don't know, based on something they've heard somewhere or read at some point.

And then generalizations are made:

All black people are dirty, all homosexuals are pigs, all Russians are spies, all Chinese are fanatics and Maoists. The focus of the assessment is on race or worldview—instead of the person. I was invited to sing in Israel. At almost the same time, I received a request from a manager in an Arab country. I agreed to perform in Israel as well as in three Arab countries. When this was heard in Israel, the invitation was canceled. There should be no boundaries for an artist. Something similar happened to a friend of mine, the poet James Baldwin, who is currently on a European tour promoting sympathy for Angela Davis. In some countries, they wanted to ban him from speaking. You should interview Baldwin sometime; he is a very intelligent, sensitive person who has stood up for gay rights in his works and in many public speeches.

du & ich

Your audience, Mahalia Jackson, consists of many young people. Girls and boys who were still children when you last performed in Germany sit in your concerts. How do you explain that?

Mahalia Jackson

That's a fact I've also thought about. It's not just in Germany, but also in other European countries and in America. The younger generation, about whom so much nonsense is said and written, is very receptive to authenticity. They can clearly distinguish between real talent, a genuine statement, and bluff. When you listen to good pop music, for example, you are amazed at how much skill goes into it, how much sensitivity resonates. And how many pop groups are there in America alone who make music for the sake of music, even if they hardly earn any money and don't become famous — yet they sing because they want to express something with their songs and because they hope to be heard and understood. To me, these young people are more serious artists than many celebrities whose names are known all over the world.

Analysis of the interview with Mahalia Jackson in "DU & ICH"

This interview with Mahalia Jackson in the magazine "DU & ICH" is noteworthy and insightful for several reasons, particularly in the context of a gay magazine in the 1970s. It offers insights into the perception of minorities at the time, the role of art and activism, and the limits of social acceptance.

At the second attempt

The interview begins with an interesting dynamic.

Mahalia initially thought it was "just another magazine" where she would be asked the same irrelevant questions she always gets. It was only when she found out what kind of magazine it was that she immediately agreed to do it. The magazine's statement that other artists pull out once they learn about its focus underscores the social stigma that "DU & ICH" had to contend with.

Mahalia Jackson's reason for agreeing to perform is the central point.

She sees herself as a member of a minority (as an African American) and identifies with the fight against prejudice and injustice. Her statement, "I myself belong to a minority, and I know that we—whether black or gay—depend on every gesture of goodwill. We also respond more gratefully than the general population," is a powerful statement of solidarity. It shows that Mahalia Jackson did not perceive the magazine as merely an erotic or niche publication, but as an "organ for a minority" fighting for recognition on the same level as the African American civil rights movement. This legitimized "DU & ICH" in her eyes and set it apart from "insignificant family magazines."

The self-image of an artist and humanist

In the interview, Mahalia Jackson repeatedly emphasizes that money is not a driving force for her. Her commitment comes from a deep inner conviction: "I want to bring joy with my songs, to convey something to the audience: My heart sings not for dollars, but for humanity." This humanistic motive is consistent with her public image and explains why she was willing to perform free of charge at a "DU & ICH" gala for elderly and needy homosexuals. Her unconditional commitment ("Yes, if you let me know in time") is a strong sign of support that unfortunately was not to be.

Fearlessness and the "big family" of the audience

When asked whether she would expose herself by performing for homosexuals, Mahalia Jackson replied emphatically: "No. My audience understands me—and I understand my audience. We are one big family." This answer is remarkable because it not only reinforces her own position as an artist, but also provides a broader definition of her audience. She sees her listeners as people who understand "the great injustices in the world and the small injustices of everyday life" and want to fight against them. This implies a deep connection and mutual understanding between her and her audience that goes beyond mere musical entertainment and is based on shared values. For DU&ICH magazine, this statement must have been an enormous affirmation.

Realism and the limits of improvement

Mahalia Jackson's answers to the question of whether "you can improve the world from the stage" are marked by a remarkable realism. She clearly denies this: "No, that would be a bold thought, unrealistic." Her view that people have changed in "insignificant ways" but that their fundamental problems remain the same testifies to a sober assessment of human nature and the complexity of global challenges. She sees her own task as "making the audience happy" and "encouraging them to think"—a modest but profound goal for an artist. This attitude is interesting because, while she actively advocates for humanity, she does not place illusory hopes in the transformative power of her art.

The core principle: rejection of prejudice and racism

The most powerful part of the interview is Mahalia Jackson's statement on homosexuality. She has "no opinion on homosexuality," just as she has no opinion on preferences for red roses or early risers. Instead, she has an "opinion on people," regardless of skin color, sexual orientation, or political/religious views. Her passionate plea against prejudice stems from her own experience as an African American: "I know from my own experience how painful it can be."

Mahalia draws parallels between racism and homophobia

"All black people are dirty, all homosexuals are pigs, all Russians are spies, all Chinese are fanatics and Maoists." For her, these generalizations are the core of the problem: "The focus of the assessment is on race or worldview—instead of the person." Her experiences with the cancellation of a performance in Israel after she had also agreed to perform in Arab countries, as well as the difficulties faced by her friend James Baldwin (who campaigned for gay rights), underscore her criticism of exclusion and lack of acceptance. This passage is a powerful testimony to her tolerance and deep understanding of the struggles of marginalized groups. It's incredible how relevant these things are today (again, or still)!

The young generation: receptive to authenticity

At the end of the interview, Mahalia Jackson reflects on the composition of her young audience. She explains this with the ability of the younger generation to "distinguish between a real performance, a real statement, and bluff." She praises "real" pop musicians who perform "for the sake of music," even if they don't become famous. This statement is not only a compliment to young people, but also a criticism of the superficiality of show business. She sees the younger generation as a source of hope for authenticity and depth, which fits well with her own humanistic and sincere understanding of art.

Resignation at the end of life?

Mahalia clearly states that she does not believe she can "improve the world from the stage." Her words are precise and unambiguous: "No, that would be a bold thought, unrealistic. No singer, no actor, no writer, no pastor, not even a politician can improve the world; it remains as it is and as it always has been."

This attitude is remarkable because it contrasts sharply with the often idealized image of the artist who brings about social change through their message. Mahalia Jackson, who herself fought for equality and showed solidarity with minorities, seems to have learned from her life experience that the fundamental problems of humanity remain, regardless of individual efforts or artistic expression.

She therefore defines her role as an artist much more modestly: she wants to make her audience happy for "two hours" and "maybe I'll even manage to make people think." That is "a lot and very little at the same time." This statement illustrates her resignation: one can alleviate suffering for a moment and provide food for thought, but the basic structure of the world and human problems remain unaffected.

It is a form of sober realism that is probably fueled by deep experiences of injustice and the slow, often frustrating struggle for change. In their eyes, the world has "only changed in insignificant ways, in outward appearances; its problems have remained the same and will probably remain so." This is a deeply resigned view of humanity's capacity for collective improvement. Their mission is therefore less a radical overthrow than offering comfort and hope in the face of an unchanging reality.

Mahalia Jackson's sober view of improving the world

The sense of resignation in Mahalia Jackson's statements is not only palpable, but crucial to understanding her philosophy. It lends a deep, almost melancholic dimension to her otherwise hopeful and committed demeanor. It is the resignation of an artist and activist who has seen and experienced the world in all its harshness and has learned to accept the limits of what an individual—even an icon like her—can achieve.

The idealism of the early years and the reality of the struggle

It is important to remember that Mahalia Jackson began her career at a time when the struggle for civil rights and against racism was reaching its peak in the US. She sang for Martin Luther King Jr., and her voice was a weapon in the fight against injustice. In this period of upheaval, belief in the transformative power of music may have been even stronger. But the 1970s, when this interview took place, were also a time of disillusionment. Despite great progress, racism, prejudice, and social inequality remained deeply rooted. Improving the world, it seemed, was a Sisyphean task.

Your statement that "humans have changed only in insignificant ways over the course of millennia" and that their "problems have remained the same and will probably remain so" is a deeply rooted, historically grown pessimism, but also a realistic assessment! It is as if you were saying: We fight and fight, but the fundamental human predisposition to hatred, prejudice, and exclusion remains. This pragmatic fatalism is perhaps a survival strategy for someone who has seen so much suffering and injustice. It is a way of protecting oneself from the constant disappointment that arises when one has unrealistically high expectations of the impact of one's own actions.

Comfort instead of transformation

If Mahalia Jackson sees her role as making her audience happy and encouraging them to think, this is not an expression of a lack of commitment, but rather a changed definition of influence. She knows that she cannot change the world from the ground up, but she can give people strength, give them a moment of joy, and inspire them to think about injustices and take action themselves. This is no less valuable, but perhaps even more lasting in its effect on an individual level. It is the comfort she provides, the hope she nurtures, and the small flame of awareness she ignites. One could interpret it this way: the belief in a grand, global transformation has been shattered by harsh reality. What remains is the realization that the real struggle takes place on a small scale, in the heart of each individual.

Their music may not save the world, but it can save souls—for two hours that may have a lasting impact on people's lives, both today and in the future!

The weight of expectations and the burden of a legend

When Mahalia was interviewed, she had long carried the burden of being an icon, a legend. She was not only a celebrated gospel singer, but also a symbolic figure of the American civil rights movement. People like her are often burdened with immense expectations: the expectation that their voice alone can change the world, that their presence can eradicate injustice, that they are an eternal source of inspiration and unwavering optimism.

This kind of public pressure can be exhausting. The resignation we hear in her words could also be a reaction to these overwhelming expectations. It's as if she's saying, "I'm only human, and my abilities are limited. I can offer comfort and encourage reflection, but I cannot eradicate humanity's deep-rooted problems." By so clearly stating the limits of her own power, she not only takes pressure off herself, but also encourages her listeners to make their own small contributions instead of waiting for a single savior. It is a humility that comes from greatness—the realization that even the most powerful voice has its limits in human nature.

This perspective shows that her resignation at the end of her life is not a weakness, but rather an impressive form of wisdom and honesty resulting from a long life spent in the service of humanity and art.

Reflektion

This interview in "DU & ICH" is much more than a "celebrity chat." It is a rare and moving historical document that sheds light on the intersections of racial and gender justice in the 1970s. Mahalia Jackson's empathy, her clear stance against prejudice, and her willingness to support a minority stigmatized by society make her an important ally of the gay rights movement.

For "DU & ICH," this interview was a huge boost and proof that their fight for recognition was understood and supported by internationally renowned figures. It shows the hope and challenges of an era in which minorities began to make themselves more visible and fight for their place in society. In addition, the interview, conducted shortly before her death, provides insight into her feelings and thoughts.

© Du und Ich Magazin 1972

A revolutionary magazine in the 1970s

DU & ICH (You & I) - a German gay magazine from the 1970s

A window into the gay world of West Germany in the 1970s

In a time of social upheaval and tentative liberalization, a magazine ventured onto the market in West Germany in the late 1960s that was to become a pioneer of the gay press: "DU & ICH" (YOU & ME). Founded in 1969, shortly after the decriminalization of homosexual acts between adult men through the reform of Section 175 of the German Criminal Code, it offered a long-invisible readership a much-needed platform.

The last issue was published in 2014

The dawn of a new era

When the first issue of "DU & ICH" appeared on October 1, 1969, it was a revolutionary step. Never before had there been a magazine available at newsstands that was explicitly aimed at gay men. This "post-September magazine," as it was initially called, embodied the spirit of change that accompanied the legal reform of September 1, 1969. Under the leadership of founding editor Egon Manfred Strauss and first editor-in-chief Udo J. Erlenhardt, "DU & ICH" opened a window to a world that had previously only existed in secret.

Eroticism, travel, and walking a tightrope

The 1970s were a defining decade for DU & ICH. The magazine focused heavily on eroticism, often featuring appealing photos of young, semi-naked models who appealed to the aesthetic preferences of its target audience. But DU & ICH was more than just a pin-up magazine; it also saw itself as a guide to a new way of life. A major focus was on travel tourism for gay men. The magazine even organized its own trips to exotic destinations such as Beirut, Togo, and Bangkok, and advertised specialized "one-man travel agencies" tailored to the needs of gay travelers.

However, the editorial team often found itself on thin ice. Following the reform of Section 184 of the German Criminal Code in 1975, which legalized pornography as long as it did not depict persons under the age of 14, DU & ICH and similar publications took advantage of the new freedoms. This led to some depictions that were considered legal at the time being classified as problematic or even child pornography from today's perspective – a dark chapter in the history of the early gay press.

Between movement and commerce

The relationship between "DU & ICH" and the burgeoning gay rights movement was ambivalent. While activists fought for greater visibility and rights, the magazine, which wanted to serve a broader audience, also had commercial interests to consider. In 1970, editor-in-chief Udo Erlenhardt expressed concern that self-identification as "gay" could reinforce the negative image of homosexuals in society. "DU&ICH" tried to maintain a serious image while also catering to the erotic needs of its readership.

A particularly controversial topic in the early 1970s was the debate on pederasty. Letters to the editor and articles discussed relationships between younger and older men. A study published in 1974, which claimed that a significant proportion of gay men were pedophiles, further fueled these discussions and shaped the image in the commercial gay press at the time.

A legacy of light and shadow

Despite these controversies, DU & ICH was an indispensable player for the gay community in West Germany. It provided a place for exchange, information, and entertainment at a time when homosexuality was still heavily stigmatized. The magazine helped to increase the visibility of homosexuals and create a space for their real lives. It is remarkable that "DU&ICH" existed until 2014, making it the oldest gay magazine in Germany.

"DU & ICH" remains a fascinating document of its time—a testament to the struggle for identity and acceptance in a changing society, shaped by the possibilities and pitfalls of that era.

©Thilo Plaesser