Renowned concert hall

© Smith Archiv/Alamy

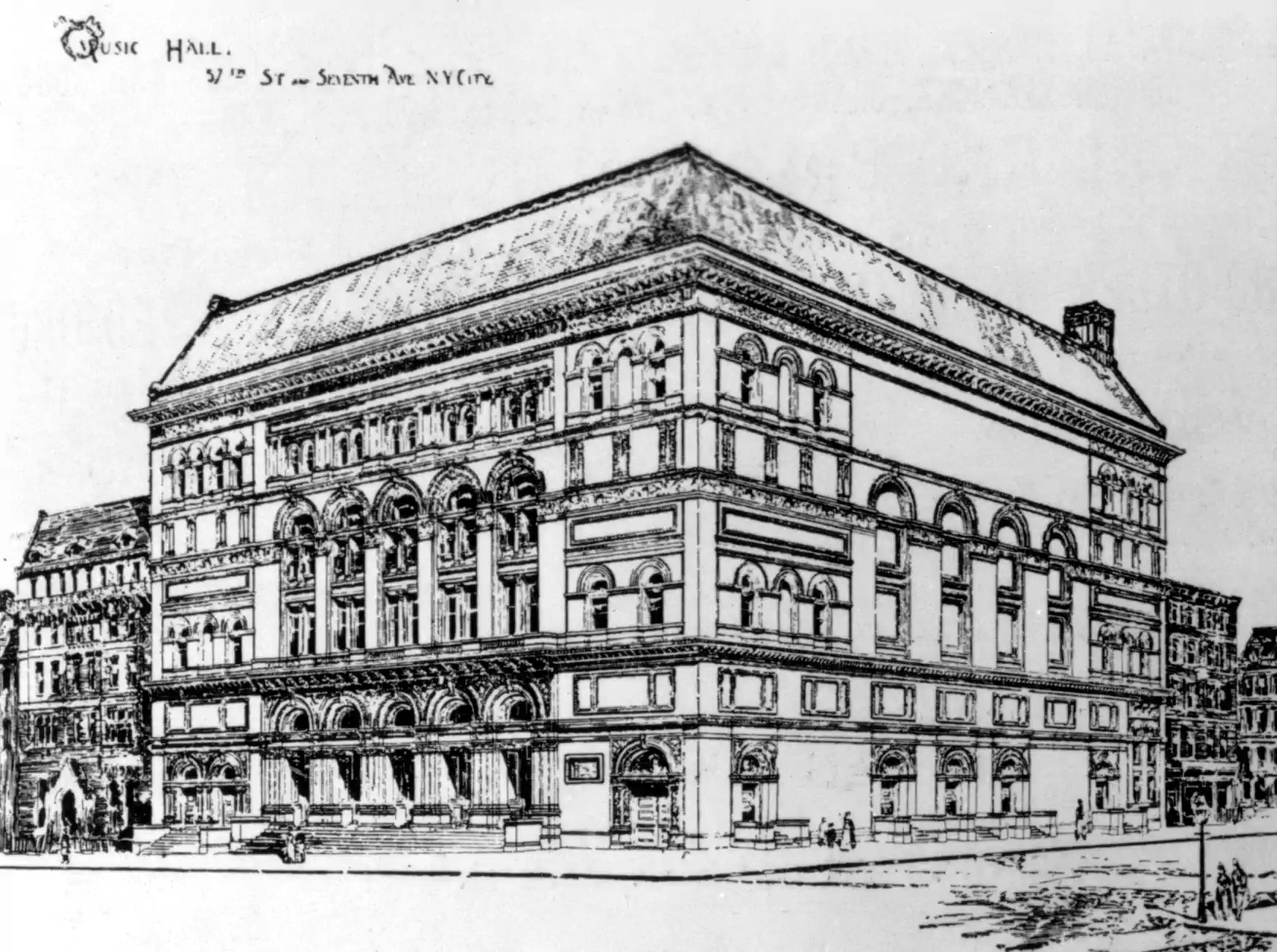

Founding and early years

The idea for Carnegie Hall originated in the late 19th century. Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie financed its construction after being convinced by Walter Damrosch, director of the New York Philharmonic, that his orchestra needed a permanent home. Construction began in 1889, and the building, designed by William Burnet Tuthill in the Italian Renaissance style, was officially opened on May 5, 1891. It was originally named "Music Hall." At the opening, the famous Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky personally conducted his works, which was a worldwide event. Carnegie Hall was one of the first buildings to have electric lighting and even had a kind of air conditioning system, whereby ice was poured under the stage before performances. However, the building was not finally completed until 1897.

Architecture and acoustics

Carnegie Hall is distinguished by its impressive Renaissance Revival architecture. It houses three main performance venues: the Stern Auditorium/Perelman Stage (the main hall), Zankel Hall, and Weill Recital Hall. The Stern Auditorium in particular is renowned for its unparalleled acoustics, which have been considered legendary since the hall's inception and are appreciated by musicians worldwide.

Historical events

Throughout its history, Carnegie Hall has been the venue for countless unforgettable concerts and events:

1938

Benny Goodman's legendary jazz concert, "The Famous Carnegie Hall Concert 1938," which brought jazz to established concert halls.

1950

Mahalia Jackson made her Carnegie Hall debut on October 1, 1950. This concert was of great significance, as she was the first gospel singer to perform at the renowned Carnegie Hall. Joe Bostic produced the "Negro Gospel and Religious Music Festival," during which Jackson's groundbreaking performance took place. This opened the doors of classical concert halls to gospel music and played a major role in making the genre accessible to a wider audience. After her debut, Mahalia Jackson performed eight more times at Carnegie Hall, underscoring her enduring popularity and influence.

1960er Jahre

Carnegie Hall was on the verge of demolition because it was operating at a loss and there were plans to build a 44-story commercial building in its place. Thanks to the dedicated efforts of the famous violinist Isaac Stern, among others, the hall was saved. The city of New York purchased the building to preserve it, and it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962.

In the decades that followed, numerous world-famous artists and ensembles of all genres performed there, including Leonard Bernstein, Sviatoslav Richter, Joan Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, Judy Garland, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, The Beatles (1964), Ike & Tina Turner, The Beach Boys, and many other greats of classical music, jazz, rock, and pop. In addition to concerts, Carnegie Hall also hosted important lectures, such as those by Booker T. Washington and Mark Twain's last public lecture (both in 1906).

Carnegie Hall today

Despite many challenges, Carnegie Hall has become one of the world's most important concert halls. It is constantly being renovated and modernized to maintain its status as a first-class venue. It remains a vibrant center of New York's cultural scene, offering a wide range of performances, educational programs (through the Weill Music Institute), and exhibitions in its Rose Museum. Many artists dream of performing at Carnegie Hall, underscoring the enduring significance and fame of this historic building.

Mahalia Jackson at Carnegie Hall

The legendary debut on October 1, 1950

On October 1, 1950, Mahalia Jackson took to the stage of the venerable Carnegie Hall for the first time. She was invited and introduced by Joe Bostic, the well-known black promoter, disc jockey, and TV sports presenter from New York, who billed the event as the "first annual Negro Gospel Music Festival."

Initial skepticism and stage fright

Mahalia hesitated at first. She felt her songs were not "high enough" for a hall she associated with opera greats such as Caruso, Marian Anderson, and Roland Hayes. She called Bostic "a fool" for inviting her and suffered from extreme stage fright. Mahalia was not usually particularly nervous, but here she was aware of the enormous significance of the occasion. On the way from Chicago to New York, she threw up and feared she wouldn't be able to sing a note. Her pianist, Mildred Falls, was also sick with fear.

An unprecedented rush

Despite Mahalia's initial concerns, the concert was an overwhelming success. Although Carnegie Hall seats less than 3,000, the concert was overflowing with an estimated 3,000 to 8,000 listeners. Hundreds of fans who had traveled by bus from various states had to be turned away. The hall was so full that 300 folding chairs had to be set up on stage to accommodate the crowds.

A transformation of the hall

Mahalia, elegantly dressed in a black velvet choir robe, gave an unforgettable performance. The audience cried, danced in the aisles, and stamped their feet—an unusual spectacle for Carnegie Hall. Mahalia even had to admonish the audience to calm down or they would be thrown out. Her performance transformed the afternoon into an ecstatic revival meeting. She sang classics such as "I've Heard of a City Called Heaven," "It Pays to Serve Jesus," and "Amazing Grace," accompanied by Mildred Falls on piano and Louise Overall Weaver on Hammond organ. Other renowned gospel artists such as the Ward Singers and the Landfordaires also performed.

Rave reviews

The concert was celebrated as Mahalia's "New York coming out" and a "gospel breakthrough." Critics were full of praise. Nora Holt of the New York Amsterdam News praised the "agonizing ecstasy" of her singing and called her an "unspoiled genius." John Hammond of the Daily Compass praised her "enormous power, range, and flexibility." These positive reviews cemented her reputation as the "Queen of Gospel Singers" far beyond the confines of the church.

Continued triumph

Mahalia's success at Carnegie Hall was no flash in the pan. Her subsequent performances, all of which were sold out, cemented her status and broke records.

Second concert, October 1951

Her second concert was also completely sold out, and hundreds of fans once again stood in line in vain. Mahalia even surpassed the audience numbers of legends such as Benny Goodman and Arturo Toscanini in this hall.

Music Inn Roundtable

Her growing influence also led to invitations to intellectual discussion panels. In the fall of 1951, she participated in the "Definitions in Jazz" roundtable at the Music Inn in Lenox, Massachusetts, where she spoke about the roots of jazz in black religious songs and discussed concepts such as "blue tonality" and the "Negro folk cry." Marshall Stearns admired her ability to add "breathtaking embellishments" even though she "breaks every rule of concert singing... but the full-throated feeling and expression are seraphic."

Third concert, October 1953, and the Columbia deal

Her concert in October 1953 was decisive for her future career. Mitch Miller and John Hammond from Columbia Records attended the performance, which shortly thereafter led to her groundbreaking record deal with Columbia Records. This contract opened the doors to national radio and television appearances and catapulted her into the mainstream. Another notable detail of this visit was that Mahalia stayed at a white hotel in Midtown, the Wellington Hotel, for the first time—a small but significant step toward racial equality.

Lasting legacy

Mahalia Jackson performed six times at Carnegie Hall, and every concert was sold out.

Her performances served as a barometer of her immense fame and proved that gospel music could reach a broader, often white audience. She often transformed her concerts into deeply emotional "religious rituals" by bringing her improvisational style and "gospel sway" into classical concert halls. Although she was aware that a more "refined" performance was expected of her, she deliberately broke the rules of concert singing, breathing in the middle of words or occasionally mangling words to preserve the authenticity and fervor of her music.

Her performances at Carnegie Hall were also an important contribution to the civil rights movement. On June 21, 1963, she appeared there at a concert in support of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to promote voter registration. She sang "In the Upper Room," demonstrating her unwavering support for African American rights.

Mahalia Jackson was mentioned in the same breath as the greatest opera singers such as Caruso, Marian Anderson, and Lily Pons, who also graced Carnegie Hall. Her successes in this prestigious hall, including the Grand Prix du Disque for her Apollo single "I Can Put My Trust in Jesus" / "Let the Power of the Holy Ghost Fall on Me," cemented her place as one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century. Her concerts at Carnegie Hall were far more than just musical performances; they were cultural milestones that forever changed gospel music and brought its undeniable power and beauty to a worldwide audience.

Post - event review

Mahalia Jackson's triumphant performances at Carnegie Hall were much more than just concerts; they marked a paradigm shift in the perception and dissemination of gospel music.

Legitimacy of a musical form

Before these concerts, gospel was primarily found in churches and African American communities. Carnegie Hall, an icon of high culture and classical singing, gave gospel an unprecedented legitimacy. Mahalia's initial concerns that her music was not "high enough" underscore precisely these established hierarchies, which she broke down with her success. She proved that gospel could be not only religious devotion, but also artistic performance at the highest level, without losing its religious background. Without this, Mahalia Jackson would not have been able to present her art.

Building bridges between worlds

The concerts at Carnegie Hall served as a cultural bridge. They brought a deeply African-American musical tradition into a predominantly white, secular context. The audience's reactions—crying, dancing, stomping their feet—showed that the emotional power and spiritual depth of gospel could be universally understood and felt, regardless of the listeners' cultural background. This was crucial for the destigmatization and popularization of gospel beyond its original niche. Catalyst for Mahalia's career

The Carnegie Hall concerts were the catalyst for Mahalia's rise to global superstardom. The consistently positive reviews in prestigious media outlets such as the New York Times and the Herald Tribune gave her a national and international reach that would have been impossible through church performances alone. The visit of Mitch Miller and John Hammond from Columbia Records after the third concert led directly to her record deal and thus to the commercialization and institutionalization of her success.

Another step towards equality

The concerts at Carnegie Hall also symbolized an important step forward in the civil rights movement. The fact that a black artist achieved such success in a formerly all-white and prestigious venue sent a powerful message of emancipation and potential. Her stay at the Wellington Hotel in 1953, the first in a white Midtown hotel, was a concrete example of the breaking down of racial barriers that made her success possible. Her later participation in civil rights concerts at Carnegie Hall underscored her conscious role as an activist.

Stylistic innovation within a classic framework

Mahalia Jackson succeeded in transferring her authentic, improvisational gospel style to a formal concert hall without losing its soul. She deliberately broke with the conventions of classical singing (e.g., breathing in the middle of a word) in order to maximize emotional intensity. These "rule breaks" were not perceived as flaws, but as expressions of authenticity and brilliant musicality, which expanded the boundaries of what was considered acceptable in a "classical" concert hall.

Conclusion

In summary, Mahalia Jackson's performances at Carnegie Hall not only established her personal legend, but also liberated gospel music from its niche, establishing it as a powerful and commercially successful art form while making a significant contribution to the struggle for social justice. They impressively demonstrated that true art and human emotion can transcend all boundaries.

©Thilo Plaesser